From one of the world’s most respected paint-makers, David Coles, Chromatopia reveals the stories behind fifty striking pigments. The book spans several time periods; here, we look at some of the colours featured from the ancient world.

Egyptian Blue

This was the first synthetically produced colour.

Invented at around the same time as the Great Pyramids were being built, Egyptian blue’s creation dates back about 5000 years. The Ancient Egyptians believed blue was the colour of the heavens and because of the rarity of naturally occurring blue minerals like azurite and lapis lazuli, they devised a way to manufacture the colour themselves.

Egyptian blue was not produced by blind chance: it was created with precision. Made by heating lime, copper, silica and natron, the pigment’s invention was a development of the ceramic glaze processes. The Egyptians controlled the firing of the raw materials with amazing accuracy, holding their kilns at a crucial temperature close to 830°C.

The famous crown of Queen Nefertiti owes its colour to Egyptian blue and the pigment was used extensively for painting murals, sculptures and sarcophagi. It spread from Egypt to Mesopotamia, Greece and the outer reaches of the Roman Empire and was used at the palace at Knossos, in Pompeii and on Roman wall paintings. Known to the Romans as caeruleum (from which the colour cerulean derives its name), it was widely used throughout the Classical Age, but the knowledge of how to make it was lost with the fall of the Roman Empire.

Discoveries made by Napoleon’s 1798 Egyptian expedition led to further investigation of Egyptian blue; and eventually, in the 1880s, the chemical composition of the pigment was identified and the manufacturing process was recreated.

Orpiment

Orpiment was the closest imitation to gold.

Its Latin name is auripigmentum (gold paint) and in the classical world, it was believed that this resemblance had deeper alchemical roots. It was even said that the Roman emperor Caligula could extract gold from the mineral.

In fact, orpiment carries a much more dangerous substance. It is a highly toxic sulphide of arsenic. The Persian word zarnikh (gold-coloured) became arsenikon in Greek and then arrhenicum in Latin, from which the English word ‘arsenic’ is derived. The Romans were well aware of orpiment’s poisonous nature and used slave labour to mine it. For the unlucky slaves this was, in essence, a death sentence.

Orpiment was used in Ancient Egypt as a cosmetic, taking its place in history alongside other deadly pigments used in makeup. It was used in painting for centuries throughout Persia and Asia, but in Europe, because of the dominance of lead-based yellows, it was most often employed in manuscripts.

A manufactured version, known as king’s yellow, was available from the 17th century. The name is believed to come from Arabic alchemy, which described orpiment and realgar as the ‘two kings’.

Both the naturally occurring and synthetic versions of orpiment were incompatible with other commonly used pigments, particularly lead-based pigments like flake white, and copper-based pigments like verdigris and malachite. It was infamous for turning them black. With the introduction in the 19th century of the more chemically inert and less toxic cadmium yellow, orpiment fell out of usage.

Woad

Woad was widely used as a dye in Europe as early as the Stone Age.

Ancient Britons covered their bodies with woad to face the Roman legions and it is said that they struck fear into Julius Caesar himself.

The first part of the woad-making process involved taking fresh leaves of the woad plant, Isatis tinctoria, grinding them to a pulp, rolling them into balls the size of large apples and leaving them to dry in the sun. They could then be stored and used at a later date. Like indigo, the dye is extracted by fermentation. Traditional recipes specify that the plant be soaked in urine under the heat of the sun and trampled for three days. After that, the remaining liquid is a yellowish colour.

The indigo molecule is the blue colourant in woad. The magical quality of indigo is that the distinctive blue colour only develops after the textiles are removed from the dye bath and exposed to air. During the dyeing process, a scum called florey, known as the flower of woad, also develops on the surface. This was skimmed off and dried so it could be used separately as a paint colour.

The fermentation process releases large quantities of ammonia. Far worse, however, is that the plant depletes the soil that it grows in, leaving an infertile wasteland in its wake. Laws were passed in medieval Europe to curb this devastation.

Although indigo was known since Imperial Rome, the more colour-intense Indian indigo was not readily available in the west until commercial quantities were imported at the beginning of the 17th century. It supplanted woad, and production rapidly declined as a result.

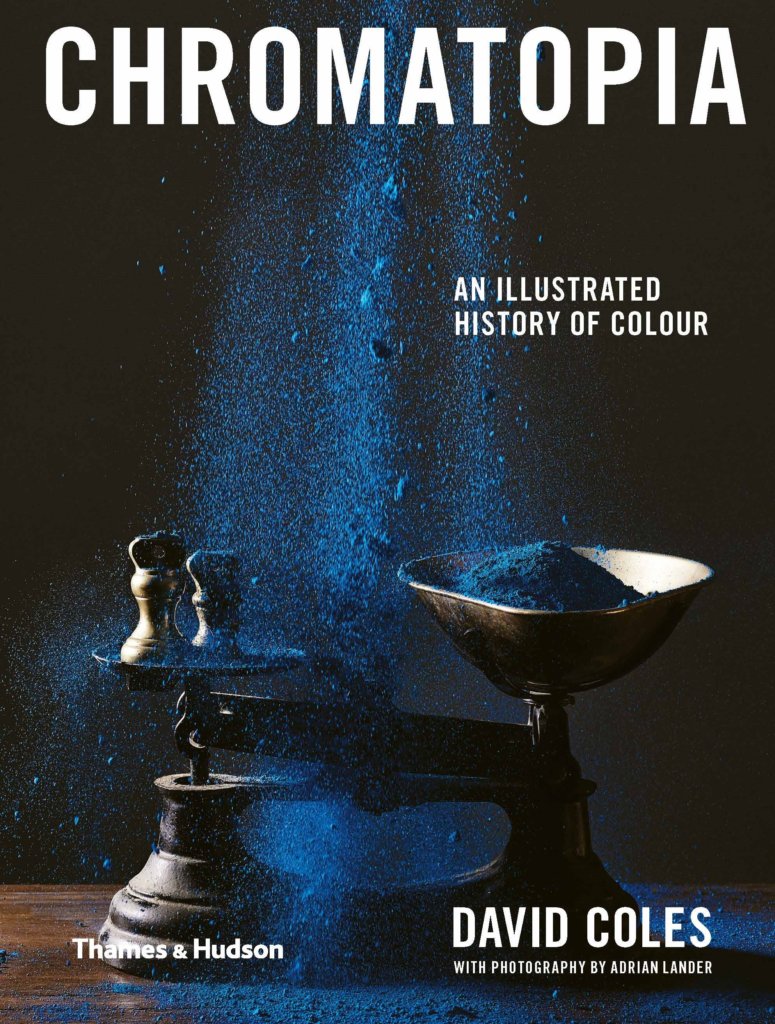

Chromatopia is available now. Text by David Coles, photography by Adrian Lander, and cover design by Evi. O Studio.

AU$34.99

Posted on May 20, 2020