Description

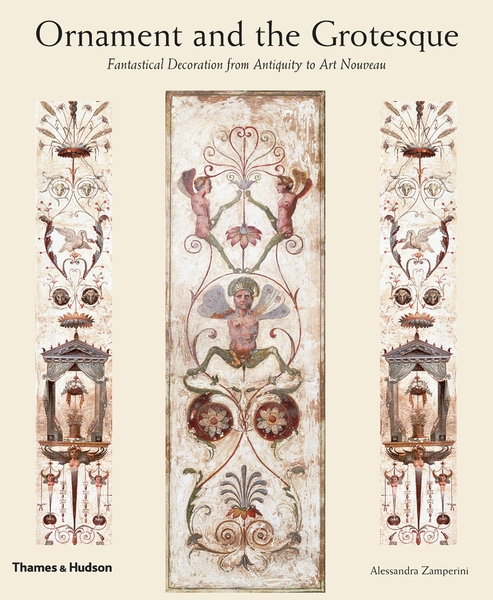

When Nero’s Domus Aurea was inadvertently rediscovered in Rome at the end of the 15th century, its sumptuous interiors not only sparked renewed interest in ancient culture but revealed an unfamiliar, playful style of classical ornament that captured the imagination of Renaissance artists. By that time this fabulous palace had long been covered with earth, and for the first explorers it was like entering a series of caves or ‘grottoes’, which is why they called the style of the painting on the walls and ceilings ‘grotesque’. Far removed from the formal language of traditional classical ornament, what they saw was something essentially decorative and only semi-serious: parodies of classical mythology, fantastic hybrid monsters, men hatching out of eggs, images of perverse eroticism, impossible architectural visions, giant butterflies, mischievous putti, monkeys, sphinxes and nightmare insects – a whole repertoire of uninhibited imagination where nothing was taboo.

Inspired by this discovery and following the medieval predilection for the fanciful and the monstrous Italian artists, including Perugino, Signorelli and Mantegna, immediately started to copy the style. On the ancient Roman precedent, mythological or allegorical scenes and motifs were arranged symmetrically without any apparent structure in terms of subject matter or scale; the Renaissance artists preferred to impose a vertical format on the loosely connected elements in order to bring a sense of order to the overall compositions.

It was Raphael’s decoration of the Vatican Loggie in the early 16th century made the grotesque into a Europe-wide fashion, and it soon became an integral decorative feature of the most lavish residences, incorporating ceramics, textiles and tapestries.

As the grotesque was disseminated throughout Europe, important new stylistic forms emerged and evolved. The first book to reveal this vast treasury, this brings the story up to the late 19th century and shows how it led eventually to Art Nouveau.