This is an edited extract from Artists at Home by Karina Dias Peres.

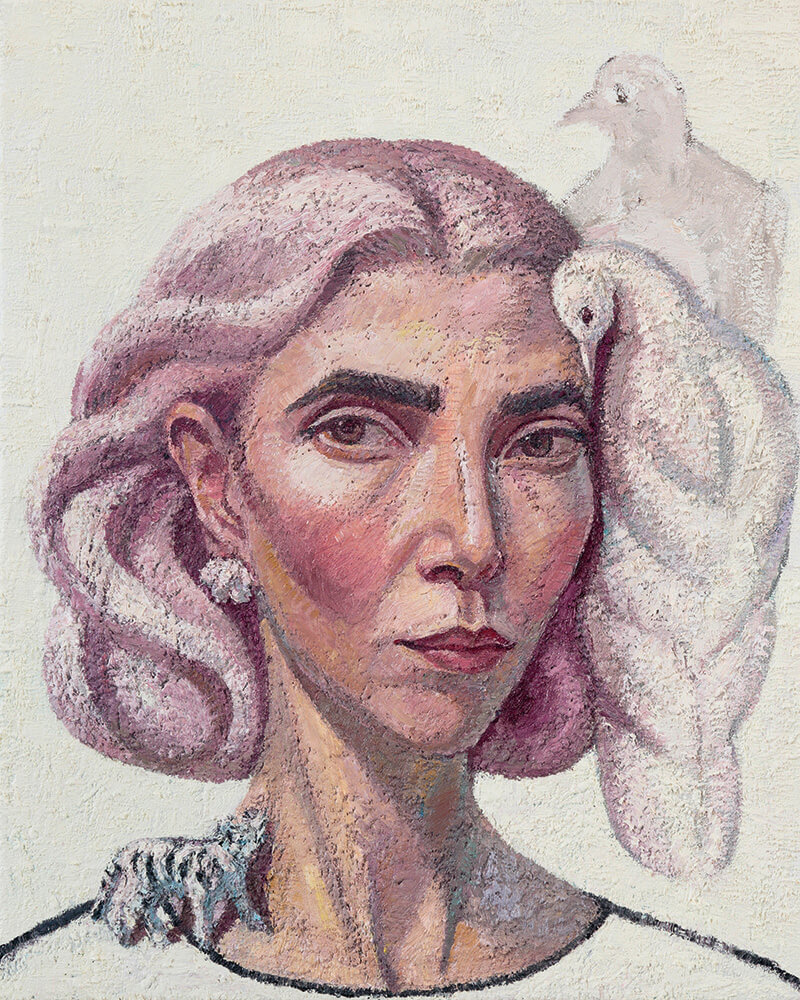

It has been said that to capture the essence of someone else, you first need to capture the essence of yourself. With a career spanning over twenty years, Melbourne-based artist Yvette Coppersmith has experimented widely with various subject matter, including still life, figurative and abstract paintings, yet she still feels a strong pull towards exploring self-portrait. During her early childhood, Yvette watched opera and ballet DVDs. She also studied and drew faces from magazines. Later on, she began depicting friends, family and herself. The direction of her early process led her towards photorealism and portraiture, and after finishing high school, Yvette started at the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) in Melbourne. She highlights that photorealism wasn’t particularly on-trend at the time but, despite going against the grain, she was recognised for her unique style and received a commendation award for her graduate exhibition. Her paintings for that exhibition were all portraits of women and included a self-portrait, a portrait of her grandmother Ida and another of her great-aunt Basia; three full-length portraits to scale, which were hung level with the floor so the viewer could meet the subject at their actual height.

During the first decade of her practice, Yvette mainly relied on photographs, life models and herself as source material to create oil paintings; these foundational years brought discipline and focus, a period in her career she ironically calls ‘slave to the image’. Sitters often included public figures who have made contributions to our society, such as Rupert Myer, the Chair of the Australia Council for the Arts, and Gillian Triggs, former president of the Australian Human Rights Commission. It wasn’t until 2009 that her taste in painting started shifting to process-driven work and abstraction, welcoming more tactile and textural qualities. Yvette works predominantly in oil on linen, and occasionally on primed jute. The layers of paint are mixed with linseed oil (and sometimes sand) to create her signature bold texture.

‘When I began painting my self-portraits, we didn’t have smartphones and social media was not part of our experience. There was a perception that you must be a narcissist to be making images of yourself, and self-promotion wasn’t as widely accepted as it is now. For centuries, artists have understood the image of the self is a construct, and a useful one to position oneself in society. Self-portraiture is a space where you can be your own imagined self,’ she says.

Yvette recalls studying make-up books by Kevyn Aucoin when she was around eighteen, and experimenting with contouring and creating images of herself. She took photos with an old film camera in 2000, and the first digital camera she purchased in 2004 had a flip-around screen to better frame compositions as references for her paintings. Ironically, she thought, ‘wow, if everyone knew about this, they’d take better photos of themselves’, never expecting the global explosion of selfies. In the past few

years, she has worked from a mirror, which is a different method from taking a snapshot. She explains that the light and detail working from life is an advantage, but poses are more limited.

In 2018, Yvette won the Archibald Prize awarded by the Art Gallery of NSW for her painting Self-Portrait, After George Lambert. After being a finalist four times, she is one of ten female artists to have won the prestigious prize in 100 years. The winning self-portrait was initially supposed to be a portrait of New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern. When Ardern wasn’t available, she thought she could still draw inspiration from her, as a call to action to inspire women and the next generation of progressive leaders.

‘Women artists are part of the rebalancing of the masculine/feminine energies at play in the world. The abuse of women and of the planet are connected. Australia has a leadership crisis in the face of a climate crisis – this isn’t a time to lose hope but to spring into action. The calling out of these injustices must continue, and the momentum and desire to ignite change as a collective is gathering,’ she says. Yvette sees a space for activism in some of her portrait works, not with protest but utilising the ability of art to connect to the human, to beauty and joy. She believes the role of a contemporary portrait painter is to take this tangible quality and position each person far beyond their media or social media platform.

You were one of only ten women to win the Archibald Prize in 100 years. What does it mean to be a woman in a predominantly male-dominated industry?

It is important to acknowledge how far we have come in the perception of women artists. The first woman to win the Archibald Prize was Nora Heysen back in 1938 and she dealt with a vastly different industry. At the time her counterpart male artists commented: ‘A great artist needs

all the manly qualities of courage, strength and endurance. I believe that such a life is unnatural and impossible for a woman.’ The media headlines about her were: ‘Girl painter is also a good cook!’ Thankfully my experience has been full of opportunities, and it is heartbreaking thinking how women artists throughout history made it against all odds. So yes, we are a very lucky generation in some ways but the fight for gender equality is still ongoing because patriarchy is structural.

Did you have any female role models growing up that influenced your career?

Anne of Green Gables and Pippi Longstocking for their strong female characters were good role models as a kid. Julia Ciccarone, a Melbourne artist who became my mentor the year I graduated from the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA). We met up and visited each other’s studios a couple of times, and that was a nice way to ease the transition from university to solitary art practice. My mum, Renee Coppersmith, who worked from home on her own business as I grew up. She has been a role model for working her own hours, being her own boss, and the hustle. I know how hard she found it juggling motherhood and work, and I am so grateful for having such a generous parent. I don’t think I could divide my time like she did without feeling resentful at the sacrifice.

As an artist, what is the best lesson you have learnt along the way?

I used to overwork to meet all my commitments, and in the past couple of years it became apparent, perhaps due to some burnout, I had been putting my relationship with painting ahead of my relationship with myself. We hear a lot about self-care, but it wasn’t in my consciousness until recently that to establish a viable career as an artist, you also need to prioritise rest and sleep.

The solitary nature of working as an artist has taught me self-reliance. I value quality time connecting with people, but I have also come to realise that the only relationship that lasts a lifetime is with yourself. As women we

have been raised to feel like we are not enough without the romantic relationship, the right body, and all the right stuff – it’s taken the past couple of years to recognise how embedded those concepts were, and into a sense of wholeness in myself.

Can you name some of your favourite Australian artists?

Grace Crowley, Grace Cossington Smith, Nora Heysen, Ralph Balson, Margaret Preston, Rah Fizelle, Hera Roberts, George Lambert, Hugh Ramsay, Max Meldrum. Also Teelah George, Oscar Perry, James Drinkwater, Jake Walker, Lottie Consalvo, Sam Martin, Sanné Mestrom, Michael Georgetti, Eleanor Louise Butt, Tsering Hannaford, Diena Georgetti.

Is your home aesthetic a reflection of you as an artist – contemporary, textural and colour oriented?

My furniture is all neutral: grey marble table, timber sideboard, linen bench seat. I can change the colour scheme by rehanging pictures. At th moment there is an emerald green theme. If I could change my house I would add more wall space and have more art on display, including more of my childhood paintings.

Artists at Home by Karina Dias Pires is available now.

AU $ $59.99

Posted on December 7, 2022