It was over a drink at a pub in West London that William Roper-Curzon and I decided to try to host residential painting holidays at Arniano. William is a painter, who trained in London at the City & Guilds and, later, the Royal Drawing School. I first met him when he was preparing for a large solo show of his drawings to be held in central London, and it was (platonic) love on first speaks.

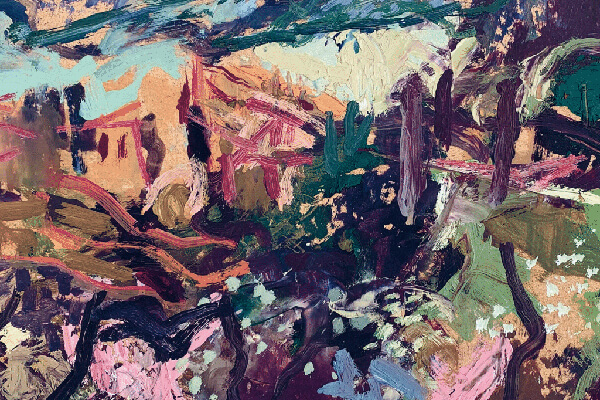

William is a hilariously funny raconteur and masterful story-teller. He has a seemingly endless arsenal of anecdotes, which have whoever is lucky enough to be with him doubled over with laughter within minutes. Aside from his company, it was easy to fall in love with his dynamic figurative and landscape paintings, all highly expressive, with strong rhythm of line and confident mark-making.

From 2010, William was often travelling on art residencies, searching for exciting places to paint. I sometimes followed to visit, which took me to Scotland, the southernmost tip of Ireland and northern Tuscany. But he also went much further afield, to Buenos Aires, California and New York. These trips, which often lasted months, were usually preceded by a greedy farewell dinner with friends and family, which I would gladly throw for him at my mother’s house in London.

It was over our drink in early 2014 that he described Arniano from his perspective as a landscape artist, and made me immediately believe that we should try to share the place I love most in the world with other people. He described what I had never been able to articulate myself – that what makes Arniano special for a landscape painter is the two types of view: ‘You have the huge vistas, the 360-degree panorama of the Tuscan hills, which are so rich in opportunity for the painter. But you also have these very intimate scenes, of beautiful plants in the garden, and the structures of the cypress trees planted by your father. It’s a mix of formality with raw nature. There is an underlying pink colour that comes through from the earth there, as well as seemingly endless sky. You are so high up that you are soaring above the valleys, and you can look down on everything before it spreads up again towards Montalcino and the mountain.’

William also had a great love for the house, feeling that ‘its ability to make anyone feel welcome’, as well as the total peacefulness, contributed to an atmosphere conducive to painting. ‘It’s incredibly quiet, there is no noise, no interruption, and a great sense that you can wander for miles to find any little area to paint. It does take you back in time there – you could be in medieval Tuscany, you would hardly know the difference.’

The concept behind the courses was that we would marry my ability to cook and host with William’s talent for imparting his knowledge of and passion for painting. Rather than creating a painting boot camp, the idea would be to ensure that students of all levels could confidently grow into their artistic ability through his charm, sense of humour, enthusiasm and encouragement. While a five-day painting course might not impart the technical ability of Rembrandt to a beginner, it would be enough time to teach our guests to use oil paints, to really look at a landscape in a manner that would make it possible to translate what they saw to canvas. In the case of experienced painters, the course would afford them the time and space to focus on an entirely new view. Either way, we wanted to curate a week in which people could be artistic, appreciate their surroundings and crack on with painting while not having to worry about feeding themselves – hopefully, making them feel well looked after and a bit spoiled along the way.

We decided to do a test run with some of William’s family – as he is number eight out of ten siblings, there were plenty to choose from. The week was fun, but chaotic and exhausting, as we had absolutely no help. I cooked, cleaned, made the beds and even modelled for paintings, but we loved it, and it was a fantastic learning curve. From an art perspective, it was a hit, and it was wonderful to see the garden dotted with people immortalising parts of my father’s garden and the view that I had always taken for granted.

While we learned so much from our guinea-pig gang, there was still a long way to go. That group had consisted entirely of friends or relations, who knew each other well and so fitted into our house-party format easily enough. We would now have to host up to twelve strangers, who would be eating together three times a day and painting alongside one another every day for a week. Kind and curious friends, relatives and godparents came to support us, and we learned with each course how to improve. But without an established reputation, it is difficult to persuade people to spend a week in an unknown house in the middle of Tuscany, with total strangers, being taught by an as-yet untested art instructor.

We advertised in The Spectator, we put flyers up in London art schools and galleries, and we asked the Royal Drawing School to send PDFs of our flyers out with their newsletter, which they kindly did – William being an alumnus and having taught in their foundation year. Finally, by 2016, following a surprise mention in the Financial Times and later features in various other publications (including The New York Times, Tatler, Vogue, The Daily Telegraph and House & Garden), we no longer had trouble filling the house, and have since welcomed guests from all over the world: the US, Mexico, Sweden, Spain, Switzerland and the UK. Best of all, we have made an extraordinary number of truly great friends

The Landscape

A peculiar attribute of the landscape surrounding Arniano is the ever-changing light. Early in the morning, there is an extraordinary mist that sits in the valley and interweaves through the hills, allowing just the tops to show above the smoky clouds. These changes bring with them new moods and shadows, drawing our painters to different views and areas of the garden throughout the day. By the evening, everything has altered again, and there are often intense sunsets, bringing silhouettes from the trees and much darker, richer, olive colours.

William encourages our painters to work on two or three paintings at any given time – going back to each one at the same time of day, on each subsequent day, in order to capture the subject in the same light. When the wind picks up, which can happen at around midday and into the early afternoon, he encourages everyone to carry on, professing that ‘it is part of painting outside … you have to learn to be in nature, to absorb it – it will make a better picture.’ Being a committed outdoor painter, this is also William’s philosophy when it comes to painting in the rain – which, on the rare days when we have downpours, perhaps half our guests will heed, while the other half scuttle indoors to draw a still life. ‘Sometimes rain is great,’ he says. ‘Often, if it’s raining on you, you will get a fabulous light and these dramatic clouds, and somewhere else in the landscape, a whole drama unfolding in front of you. You learn to be instinctive, to get things down quicker, to try to capture the feeling of being in it and experiencing it.’

An obvious feature of the Tuscan landscape, which begs to be drawn or painted, is the olive trees, which unfortunately are also famously difficult to translate to canvas. ‘Olives are hard to paint because they are dense as well as airy,’ says William. ‘I always tell my students that it’s like trying to paint a shoal of fish. It’s incredibly difficult. It’s a commitment, but once you get into it, and realise that it isn’t one mass of leaves the same size, that perspective plays its part – the leaves which are closer to you are bigger, and the further away ones smaller – it’s very worthwhile. As with any challenge, it becomes satisfying once you’ve resolved it, but it’s definitely not easy.’ Having surmounted that first hurdle of painting at Arniano over the past six years (to the point where he could ‘paint olives in my sleep’),William finds that it is the horizon that draws him back again and again. ‘Somedays you see a ridge, and then others you think, “Oh my god! There’s a whole other town I never knew was there. It looks just like a medieval Italian painting.” There is a never-ending change of light and endless possibility.’

An important thing to remember when looking at a landscape and composing a view to paint is the foreground. ‘You may see a beautiful view and want to paint it, but the whole reason why it’s beautiful is what’s leading up towards it. People tend to forget about the thing that is right in front of you to help balance it out. Painting is all about balance. A ridge that is miles away, without the surrounding context, doesn’t have the same impact as what you are actually seeing.

Painting with Oils

Oil painting has such an illustrious history, and so many famous names are associated with it, that attempting to paint with oils as a beginner can be a much more daunting prospect than it need be. Doubtless, it is a faff. It’s messy, the paint takes a long time to dry and you need the right kit as well as space in which to set yourself up. But it also brings a huge amount of freedom and room to experiment. You can change things, work things out, and build up layers of colour and shapes. As William puts it: ‘Oils are great because you can fill a large area very quickly, but equally you can wipe or scrape them off if they’re not right. Each mark is less of a commitment than with, say, water colours. The different density of the colours with the mediums means you can make a colour almost transparent, or really thick, and certain colours are more transparent than others. Often the very dark colours, like ultramarine and some greens, are very rich colours, but also very transparent. If you add a warmer colour, they become more opaque and dense. Equally, because there is so much freedom provided by oil paints, there are a lot of things to think about. It can be daunting, but for the better, as you have more to play with and to experiment with, to find out what your style is like.’

As with cooking, painting with oils becomes less daunting every time you do it, as your confidence grows and you get used to the feel of the paints, the brushes and the medium. By the end of the week at Arniano, we always hope that everyone has done something they are proud of, at the same time as having figured out their own way of doing things. William tries to teach in such a way that everyone comes up with their individual style of painting. He disapproves of hard and fast rules, and dislikes the idea of anyone leaving Arniano and simply going on to paint like him. He wants each student to be able to do it on their own, to go home and enjoy it.

The start of the week is focused on finding something that each student is interested in painting. William will walk the students around the garden until they find a subject that captivates them. Quite often, if he sees that a student is good at doing close-ups of plants during the first morning of charcoal drawing, he’ll set them up in front of the fig tree with some nice, dark shadows behind, and ask them to paint the pleasing, interlacing fig leaves. Sometimes a student might not want to paint the landscape at all, but would rather stay indoors to paint one of my mother’s ceramics. These people are usually those whose knowledge or natural interest lies in design. Even so, this exercise often leads them back into the garden to have a go at landscape, because they feel more confident attempting to paint ‘shape’ and ‘form’ outside having had a practice run at capturing a Granada bowl in the kitchen.

Because the guests have just under a week – it is a rarity to have time and space where you can focus purely on oil painting – William’s philosophy is that everyone should just get on with it, and procrastinating is sharply discouraged. After an initial morning of charcoal drawing together, to get everyone’s eye in and to get them to think about composition, everybody is dropped in at the deep end and told to start painting. Although it’s only a week, it’s a lot to absorb in a short amount of time, and everyone is exhausted by the end, having done a lot of work.

Starting a Painting

Before you start painting, you will need the following:

- a minimum of three round-headed and three flat-headed sable brushes for oils

- non-toxic vegetable-based medium, or turpentine

- linseed oil

- a basic set of oil paints, which includes all the primary colours

- a large tube of white, zinc and/or titanium (very useful)

- any additional tubes of paint in colours that capture your imagination (we love French ultramarine blue, cerulean blue, lemon yellow, cadmium yellow, yellow ochre, Venetian red, cadmium red, crimson alizarin, burnt umber, raw umber)

- primed boards to paint on – you can prime wood boards yourself by coating them with white emulsion, or buy ready-primed from any art store (we order ours from the wonderful art suppliers Zecchi, in central Florence).

The key to enjoying the process of painting is to set yourself up fully at the beginning, to make sure you are comfortable and to have everything you need. You should also have some cloths for wiping your brushes, and two pots of medium: one pot of pure medium, for cleaning the brushes, and another pot containing half linseed, half medium, to add a little gloss to the paint. Some people prefer a drier finish and omit the linseed – this can also be beautiful. It is entirely down to preference and personal style. Regularly cleaning your brushes is imperative, in order to keep your palette clean and the colours distinct. William is strict about everyone cleaning their brush in-between changing colours – the result of not doing this can be a dreadful grey mush.

The next thing is to make sure that everything is in its proper place. For instance, if you’re right-handed, arrange your easel to your left, so that you have your right hand at the view and your palette in front of you (and vice versa if you are left-handed). If everything is in its proper place, then you won’t have to keep moving around. Simple, good habits such as these make a huge difference.

Once you are set up, look at the view and decide on a colour palette (a set of dominant colours), before mixing these up using different colours to achieve the one colour you are after. At Arniano, the landscape has a lot of pinks, rich greens, blue skies and sulphur-coloured clouds, but it isn’t necessary for the colours to be realistic. It’s how colours work next to one another that is interesting, as they can have an amazing effect on each other. If you mix your colours thoughtfully before you start, you can create a tension between them. You can also dive straight in, without having to fastidiously mix as you go along. If William sees that someone is struggling with choosing colours to commit to canvas, he will open one of our artbooks and choose a painting by, for example, Gauguin and say: ‘I want you to make those colours and apply them to this view.’ This stops people fixating on capturing the exact colours as they see them, and helps them to learn to play around with colour and to gain confidence.

The best way to get started is by squinting your eyes. You will be able to see the rough shapes within the landscape, as well as the darkness and the light, and how they interact, without being distracted by the details. Once you have determined these elements, quickly block them in. By getting rid of as much of the white on the canvas as possible, you are setting the story. A ‘blank canvas’, so full of endless possibilities, can actually be upsetting. Once you get some paint on it, it won’t freak you out so much, and you can keep building up the detail and begin tweaking. William believes that the main thing for beginners to overcome is a tendency to get too precious about a painting, which can lead to procrastination. This can be fatal, as anxiety about what to do, or what not to do, will remove the pleasure from the process. Painting is purely for oneself – a way to feed your own soul, no one else’s. When a painter dithers, or hangs back, William will appear with barks of, ‘Just slap it on, it doesn’t matter.’ The beauty is that you can always start a new one if you hate the end result.

William’s advice to anyone who is starting out with oil painting is to be brave and to keep doing it, to try to get into the habit of painting as often as you can – every day if that’s possible, or even once a week. Be as consistent as you can, and keep looking at the works of other artists, at works that you like for their composition, colour palette or technique. It’s not cheating to do that. Quite the opposite. You are doing it for inspiration, to see what clever things people come up with that you really like, and that you would like to emulate.

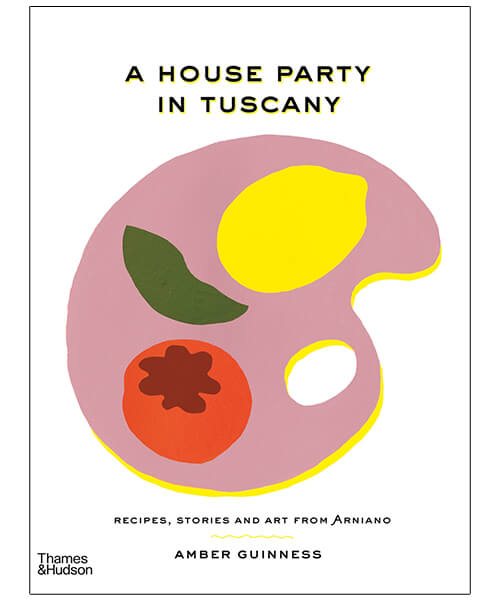

This is an extract from A House Party in Tuscany by Amber Guinness.

A House Party in Tuscany by Amber Guinness is available from 29 March.

AU $65

Posted on March 23, 2022