Landscapes are, in large part, defined by their plants. At the global scale, plants define Earth’s biomes (environments characterised by particular climates, plants and wildlife, such as grasslands, forests, deserts, etc.). At the continental scale, they define ecoregions and ecosystems. Plants are at the core of life as we know it. They fix the almost inexhaustible energy that thunders down to Earth’s surface from the Sun into a form that makes it accessible to all life on Earth. They are truly remarkable. Without plants, we would have no food or oxygen. In many ways, the success of our species depends on a successful relationship with plants. It is through plants that we humans manipulate and shape the world around us. It is through plants that our people care for Country. It is through plants that we made this continent. And it is through plants that we will rescue Country from its mishandling since the British invasion.

THE BOLIN BOLIN STORY

To begin to get a picture of the past, we need look no further than the city where I have lived most of my life: Narrm (now known as Melbourne). The Narrm of today is a radically different landscape from what it was under the custodianship and management of the Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung/Bunurong. Where today there is a concrete jungle surrounded by what feels like an interminable urban sprawl, there was once a landscape of vast wetlands and grassy plains focused around where Birrarung (now the Yarra River) met the sea. This whole region was a high-production environment where fresh water, salt water and land met. A system in which the Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung/Bunurong managed more than 150 species of grass, twenty-four species of rush and sedge wetland plants, more than 180 species of birds (including culturally important species such as magpie geese, brolgas, swans, ducks, emus and bustards), more than twenty species of fish and eels, and two species of freshwater crayfish. It is no surprise, then, that within five years of first ‘discovering’ Narrm, more than 20,000 British and other settlers had flooded to the area, along with more than 700,000 sheep.1 Like much of this continent, the British capitalised on what was a deliberately curated and managed landscape, while giving absolutely no credit to the people who created it.

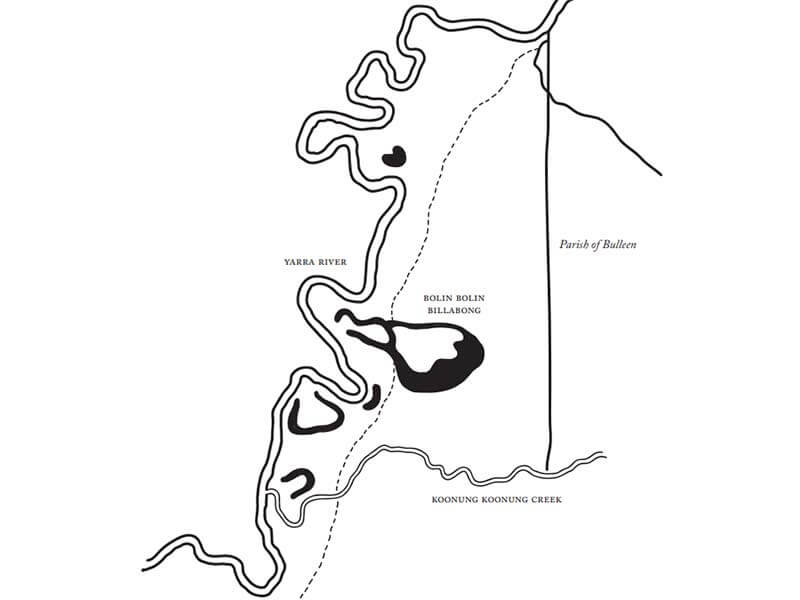

Further up Birrarung lies a series of billabongs (also known as oxbow lakes) of significant importance to Wurundjeri people to this very day. Billabongs form when sinuous rivers on broad, flat floodplains suddenly change course and leave behind an often horseshoe-shaped lake that was once part of the river. These wetlands continuously form and slowly fill up, eventually becoming part of the floodplain. One of these sites, Bolin Bolin Billabong (Figure 3.1), was the meeting place for hundreds of Wurundjeri for months at a time, where they would feast on eels, fish and other products of their careful curation of their Country. So important is Bolin Bolin Billabong that it was the site chosen by the Wurundjeri as their preferred place to settle while attempting to negotiate an agreement with the British authorities after invasion. This request was rejected, as the British desired the productive land for themselves.

Today, Bolin Bolin feels like a forgotten ruin in the inner suburb of Bulleen, a suburb which derives its name from the billabong itself. A busy thoroughfare of trucks and traffic bustles past the site continuously. The water has a bright orange tinge and the mud a deep black colour that reflects a wetland heavily polluted and starved of care. Giant branching beal, or river red gums, dot the shore, relics of a former time, when Country was more open. Now, these giant bicentenarians are crowded underneath by shrubs and young trees jostling for space and light. This new generation will grow tall and straight, not having the luxury to spread wide in open Country, free from competition. Further towards Birrarung, the sound of the passing trucks fades and kookaburra laughs can be heard, kangaroos glimpsed among the dense weed-infested shrubbery. Happy strollers frequent the paths, walking their dogs in what they no doubt think is the bush, much as it was before the city grew too big.

While Bolin Bolin is forgotten to most, it is not forgotten to the traditional custodians. To them, it is as important as ever. It is through this place that I first collaborated with the Wurundjeri. I had previously learnt how important this and other remnant wetland sites were. I had also heard of how they were working towards rewatering the billabong to improve its health, as it is currently starved of connection to Birrarung by the heavy regulation of water in the Birrarung catchment – ‘Starved from its mother’, as Wurundjeri elder Uncle Dave Wandin eloquently and accurately puts it.2 I offered my tools to the Wurundjeri to see what secrets of the past were stored in the sediments of Bolin Bolin. After all, this place was a veritable supermarket. A jewel in the landscape. After talking with Wurundjeri on Country at great length, it struck me how important this place is and how the overgrown and polluted state of the site was like a wound for them.

READING HISTORY

My work lets me step back through time in any given place. Wetlands are a portal to the past. Think about all the stuff you breathe in: smoke, dust, pollen, chemicals, bugs, bacteria, and so on. They are all released into the atmosphere and mixed around until they eventually settle on the ground, on your skin, on top of your fridge, under the couch … you name it, if an object sits around long enough, it will start collecting atmospheric information. Ever been out to the garage, poked around and blown the dust off that old wooden chest, a collection of National Geographic magazines or a vinyl record? You, in effect, are removing information that has collected day after day, year after year, waiting to be read. Given the right tools, you can read that book. That natural archive.

Natural archives abound out in the world. They include the sea floor, stalactites and stalagmites, tree rings, bogs and, last but certainly not least, lakes. Lakes are ideal sources of environmental data, gathering information from the atmosphere, depositing it deep underwater and preserving it for thousands or even millions of years. This is a story waiting to be told. A story that gives us a glimpse into the past. A window through time.

So, on a boiling hot day in January 2019, and with a crowd of keenly interested Wurundjeri, I set to work extracting a sediment core from Bolin Bolin Billabong. This involved constructing a pontoon, which was then floated to the centre of the billabong. From this platform, I could carefully drill down into the bed of the billabong, taking a sample of the layers of sediment from beneath the water. I am always somewhat nervous when coring. Not only because everything I do in the laboratory after this point is dependent on getting it right at this stage, but because I know I am unearthing someone else’s story. I know, when working on this continent, that Country was cared for and that I will be, in some way, glimpsing into that care and into the lives of the people who cared for that Country. This time, it felt like I had the weight of the past and the present Wurundjeri with me.

Around six hours – and some six meters of sediment and river gravel – later and the job was done. I had in my care the entire history of Bolin Bolin Billabong, from when the river changed course to make the billabong through to that hot January day. After two years of pandemic interruptions and tedious, time consuming lab work, Bolin Bolin’s secrets were revealed. And never could I have imagined the story it would tell. The power it would provide the Wurundjeri and all Aboriginal people. The power to be believed. The data produced by the very Western scientific system that has disempowered our people for centuries. Data to back up the knowledge of our people. That this is, and always will be, Aboriginal land. True to form, Bolin Bolin is indeed a special place.

A YOUNG BILLABONG

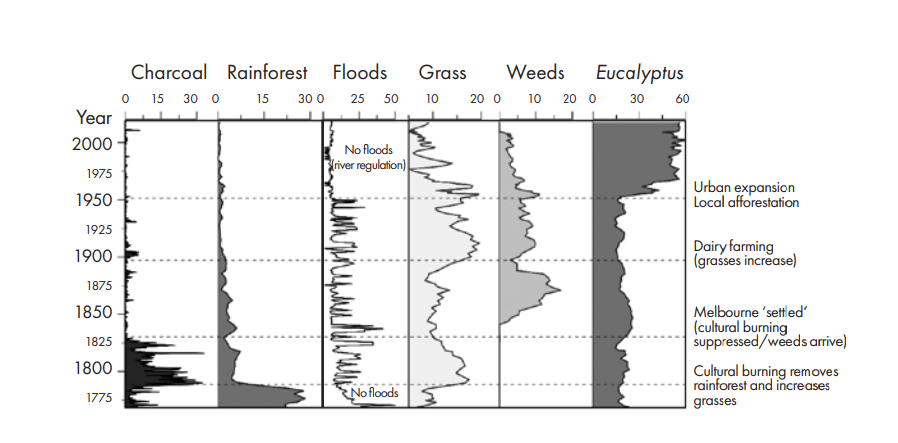

Bolin Bolin Billabong is quite young, having formed in the mid to late 1700s. This could come as somewhat of a surprise until you realise that rivers are always evolving. The present-day Bolin Bolin Billabong is one of more than fifty billabong features still visible along this section of Birrarung and lies adjacent to a larger and more ancient billabong under what is now the playing fields of an exclusive private school. Immediately after forming, the vegetation around Bolin Bolin Billabong was a fern-rich rainforest dominated by myrtle beech (Nothofagus cunninghamii). That’s right. Rainforest. Right within the lands of the Wurundjeri, there was rainforest. The closest rainforest to Bolin Bolin today is 30 kilometres away in the mountains to the east of Narrm, whose surrounding environment is considered unsuitable for this rainforest type today. In the past, there was enough rainforest growing along Birrarung that when this billabong formed, the rainforest was able to move in and capture the site almost immediately. Another interesting feature of this period is the absence of any flooding for more than twenty years while the rainforest surrounded the site.

Rainforest in Victoria is now almost exclusively restricted to the high country, in areas protected from fire. It seems that, unlike the past 180 years under British control, the Wurundjeri were able to manage fire on Country in a way that allowed rainforest to persist near sea level in Narrm. This should not be a surprise, given the ample evidence from across the continent of Aboriginal people actively protecting fire-sensitive plants via our detailed and sophisticated manipulation of fire and its influence on the structure and connectivity of fuel. It is this fine-scale management that makes Aboriginal-managed landscapes more diverse than unmanaged landscapes. It is the detailed knowledge of plants, landscapes and fire that this continent was built with.

What happened next in the story of Bolin Bolin Billabong is, in my humble opinion, the most noteworthy and important offering from the sediments I gathered. Within twenty years the Wurundjeri had removed the rainforest surrounding the site with fire. It is clear that there was still rainforest nearby, but it was deliberately and systematically removed from around Bolin Bolin Billabong. Immediately following the removal of the rainforest, Bolin Bolin Billabong experienced regular flooding from Birrarung. The opening up of the vegetation at the site, the manipulation of what plants were growing there, allowed floodwaters into the site more readily (see Figure 3.2).

This act is a powerful one – and a powerful statement. Aboriginal people deliberately altered the landscape to suit them. Cool temperate rainforests, while containing some useful resources, are generally poor in commodities. Billabongs connected to rivers via regular flooding, however, are incredibly rich in resources. Eels and other fish need connection to rivers and waterways to complete their life cycles, while regular flooding brings nutrients and sediments that are critical for the health of the entire landscape. The speed at which the Wurundjeri acted to convert the new billabong to their preferred state indicates a system of management that was reflexive and reactive to the constant addition and removal of billabongs within the floodplains of Birrarung; a system in which people were continually working to maintain productive and predictable Country.

We have little understanding of how the arrival of our people influenced the landscape of this continent. This is in part because it was so long ago that there is very little oral or physical evidence to draw on. We don’t even know when our ancestors arrived here, only that we have been here long enough for more than 3000 generations of people to have lived and worked on Country. Long enough for ‘forever’. We do, however, know that we have worked with fire through much of our traceable history, and that humans have used fire for more than 1.5 million years. A large part of this time has been devoted to using fire deliberately to modify landscapes by inserting more grass. Today, many Indigenous and local people continue to use fire for this exact purpose.

GRASSLANDS

Grass is at the heart of the story of the country now called Australia. If one thing can be said to bind all human endeavours prior to the industrial revolution (and likely since), it is that humans depend on grass. Increasing the grassiness of landscapes is at the core of most of our landscape management. Grasses produce the grains on which the world is almost entirely reliant, and they form the food of almost all the animals we consume. And as evidenced at Bolin Bolin Billabong, a shift to a more grassy landscape can also activate and help bring renewed life to local waterways. This deliberate manipulation of Country using grass has occurred throughout human history, and for tens of thousands of years on this continent.

Thus the first impressions white people had of this land were entirely based on plants, and on grass particularly. The south-east parts of our country were so reminiscent of the manicured English countryside that almost every written account was full of superlatives describing the scene as a ‘gentleman’s park’ containing some of the ‘finest meadows in the world’.3 Boon Wurrung/Bunurong Country, surrounding what is now known as Port Phillip Bay, where I have lived most of my life, was described as ‘enchantingly beautiful’ with ‘extensive rich plains … having the appearance of an immense park’.4 Yet, unlike the ‘gentleman’s parks’ in England, which were intensely curated estates, our Country was deemed to be ‘natural’. In that same passage, the author concludes that Boon Wurrung/Bunurong Country was ‘a lovely picture of what is evidently intended by Nature to be one of the richest pastoral communities in the world’5 (emphasis added). Of course, this was no happy accident of nature. The Indigenous peoples of this continent were working the land, but in a very different way to what the British could understand.

In the (apparent) absence of evidence, humans fill in the gaps using their understanding. This understanding is wrought from our ontology or ‘worldview’. The British saw our lands, but they did not see us. Having long since lost their connection to fire on the journey towards their idiosyncratic type of agrarian system, developed on incredibly fertile soils in a remarkably stable climate, they did not have the skills required to read our Country managed in this way. They could not see past the missing fences and farmhouses, or the absence of familiar farming equipment. Worse, however, is the fact that these biases were compounded with other even more harmful and pernicious misconceptions: primarily, deep-seated and deeply flawed beliefs in European racial superiority.

References

1. In conversation with Uncle Dave Waldin.

2. Jack Banister, ‘Beneath Modern Melbourne, A Window Opens into Its Ancient History’, The Guardian, 26 December 2019, <theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/dec/26/beneath-modern-melbourne-a-window-opens-into-its-ancient-history>.

3. James Boyce, 1835: The Founding of Melbourne & the Conquest of Australia, Black Inc., Melbourne, 2011.

4. Boyce.

5. Boyce.

This is an extract from the latest title in the First Knowledges series, Plants: Past, Present and Future. The chapter this excerpt is taken from was written by Michal-Shawn Fletcher.

Plants: Past, Present and Future by Zena Cumpston, Michael-Shawn Fletcher & Lesley Head is available now.

AU $24.

Posted on October 12, 2022