Words for Lucy

My daughter Lucy died on 10 November 2004, in the morning, at the age of thirty-eight. She lay on her bed for a sleep, with her cat beside her, and her heart stopped. It was, I like to think, a death of her own manner and choosing, though I doubt she did this consciously. My business is words. I put these together, my words, hers, other people’s, in celebration of her life and of our grief for her loss of it, and ours of her. Not all the words are about her, but they are all for her.

Love is so important to us. We so much need it. We can’t do without it. What we don’t realise at the beginning is the price it comes at. When we kiss the lover, when we marry the beloved, when we nurse the child, there is such perfection, such joy, we do not know the cost that is beginning to be incurred, and the paradox that the greater the love the greater the price. Though, I do think a child often comes with fear; fear skulks through the wide open door of joy, it casts its shadow and a little shiver chills us, even if we don’t entirely recognise it. Until the day of reckoning comes.

The price is loss. I have lost my husband, and my daughter. As I write these words in 2004 – it’s not that date any longer, this book will have been eighteen years in the writing, such things don’t come easily, you have to wait for them – I have a son, I have a new husband. I am building up further dreadful debits and may one day be asked to pay them. I say to my son, Make sure you don’t die for a long time, and he promises. But he can’t be sure. John, the husband, is several years younger than me, and very fit. But one of us will lose the other, one day.

You could choose to live without love and then there never would be loss. But who would want to do that?

Love equals loss. But it takes a while to twig.

I see my son James becoming aware of such things. He pays attention to me, I am his only close relative left. When I die there will be nobody at all of the generation before him, he will occupy that rather chilly eminence of the oldest in the family. There is an uncle by marriage, no aunts, some younger cousins who are all quite attached to one another but not in close contact because of geography, and it is much the same for his partner, she has a lot of cousins but not nearby. He is hanging on to me, and I am supposed to hang on to myself. But I sniff the air of mortality.

At the end of 2016, as we were waiting for his son to be born at seven o’clock the next morning, James informed me that I had to live another twenty years to see my grandson into adulthood. Mm. I doubt that is going to happen.

Beginnings

Memoir | 2021

This memoir isn’t very chronological. It doesn’t start at a beginning and go through to an end. As you might imagine a photo album, beginning with birth, through babyhood, being a toddler, school, growing up, and so on and on. No, time and memory seldom travel together. When I wrote my family saga novel Lovers’ Knots I was interested in getting the content of a saga without the massive proportions, and I came up with the image of a box of photographs. You pick them out at random, and so the story is told. This memoir is another such box of snapshots. You find your own way through the story, from random details. That said, it does begin with Lucy’s birth.

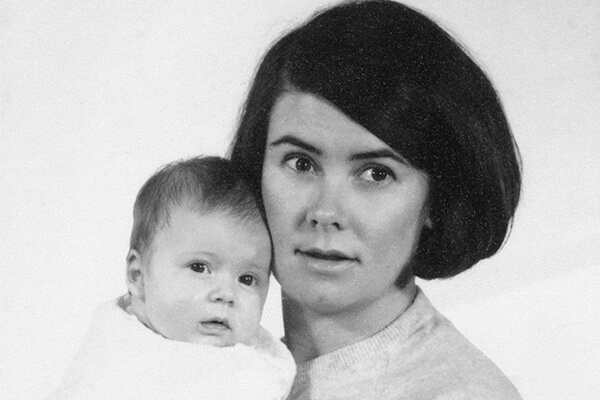

Tasting the air | 1966

When Lucy was born she tasted the air. She had a round little golden head – later doctors said she was jaundiced but when she was born she was golden, and very pretty, with smooth cheeks and no wrinkles or jowls. She lay in her crib on her back, put out her tongue and tasted the air. Very thoughtfully, as though she was testing this new medium that she found herself in. Quite voluptuously; she was offering herself a sensuous experience.

She seemed quite healthy then, though tired after a long labour, from early one morning to about three o’clock the next. It was another day before they decided she had a problem, and took her to the premmie nursery and put her in a thing called a Crown Street 10 box, which was a five-sided cube of a kind of perspex, a bit bigger than her head, into which oxygen was fed. That was when the doctor, who was a practising Catholic, said, If you believe in having babies christened, then christen this one. We didn’t believe in it, but we did christen her. Maybe to keep terror at bay; we knew what his words meant. It seemed important that some small ceremony should mark her short life. The archdeacon who had married us came from the church of St John’s, a church much older than Canberra, belonging to the nineteenth-century homestead of Duntroon, and baptised her. Perhaps he thought we were afraid of her getting lost in limbo.

The premmie nurses decided she wasn’t any good at breastfeeding and got her on to bottles, with my milk expressed. When James was born he did exactly the same thing, he choked and gagged and couldn’t take the milk. I was heartbroken, and suddenly back in that terrible time when we thought Lucy was going to die. I panicked, and wept, it was all happening again. But then a wise nurse looked and said, The poor little mite is being drowned. She made me lie on my back so that the milk did not flood out and make the baby choke, and we did that for a good twelve months. I organised myself so I lay on the sofa or the bed, holding a book in one hand, the same arm cradling James, the other hand holding the nipple so he could suck comfortably. We spent vast amounts of our days, and at first nights, lying around like this, having a lovely time.

And I realised that if Lucy hadn’t been in the premmie nursery, or if there had been a nurse wise in the ways of feeding babies, we would have worked out that Lucy’s problem was not that she couldn’t suck, but that she was being drowned, and so choked. She could have been breastfed. It is one of the sorrows of my life that she wasn’t. I think she needed to be, I think she might have been less anxious in her childhood and adult life if she had had that long loving comfort. It might have given her a useful bulwark against the fearsomeness of 11 hospitals and medical procedures. A suckling baby lies, and dozes, and drinks a bit, taking just as long as anybody will let her. But a bottlefed baby, there it is, drink up, all gone, that’s it. And other people want to do it. They like to think they are helping you, but it would be better if they did the dishes, and left this important task to you.

I am not a person given to regrets. I know they are pointless, what has happened is, it cannot be undone. But I cannot stop myself regretting that Lucy was not breastfed. For my sake, of course, the convenience of it. But I would not still regret that, forty years later. It is the comfort and the cosseting, the long lazy times spent in this milky haze of mutual delight, that I am so sad she missed.

At three weeks old she was flown to Melbourne, to the children’s hospital. It was thought that I shouldn’t go, that it would be too much for me. The cardiac physician did not think the breastfeeding mattered, he said that she would be better off staying with bottles. Until then I had thought that as she got older and stronger perhaps she would be able to cope with it. No, he said, you are only distressing yourselves. He was wrong, I know now, we could easily have done it. My milk drying up was one of the most agonising things ever to happen to me. I was ill for some time. And it wasn’t just the physical response, it was sorrow for the loss of something that I believed was so essential for the both of us. Physically, Lucy thrived on bottles. But I think that, psychologically, she missed out.

The specialist in Melbourne (the Canberra GP had wanted Sydney, the pediatrician Melbourne; the senior man won, which was harder work for us over the years, since Sydney is much easier to get to) looked at her and said, Well, she has got a pretty funny heart, but she’s okay, she’s managing. We’ll keep an eye on her, that’s all. He did that, for nine years, and then she needed her first open-heart surgery. These days they would have done it much earlier and it might have all worked better, but that is not something one can dwell on. The very 12 best was done, it was all quite pioneering, she was one of the oldest patients with her condition, the others hadn’t survived.

Dr Venables, the cardiac pediatric physician, was able to make a more precise diagnosis than the funny heart. She was born without a pulmonary valve. This meant that when her heart pumped blood to her lungs there was no valve to close and keep it there. Her heart compensated, pumped extra hard to make up for what gushed back. But the result was an enlarged heart, and a very much enlarged pulmonary artery, so her lungs were compromised by this. The solution, to fix in place a tanned valve, in this case a pig’s, was considered better left until she was as big as possible, since it wouldn’t grow with her. It had to be replaced when she was twenty-one because it had calcified; apparently this is normal, teenagers produce a lot of calcium. The second time it was a tanned human valve. The valves worked well, it was the much enlarged pulmonary artery that was the problem.

When she was born, my husband had two nuns in his class. He was a lecturer at the Australian National University in Canberra at the time. Oh, Graham, one said, I see you have named your daughter for two child martyrs. Lucy Beatrice. Of course that wasn’t our intent, we liked the names for their beauty and meaning.

This is an extract from Words for Lucy by Marion Halligan.

Words for Lucy by Marion Halligan is available now.

AU $32.99

Posted on April 13, 2022