Gardens botanic(al)

My visit to Padua was at the start of a seven-week holiday in Europe with my wife, Lynda, part of a three-month break from my job as director of Sydney’s Royal Botanic Garden. It was time to recharge and refresh, but also to do a little writing if I could find the inspiration. In the prospicient timescale of botanic gardens, I was, after four years, still a newbie in my job. My best known accomplishment so far was a ‘chainsaw massacre’ of fig trees in Sydney’s Domain. I was doing regular radio interviews and publishing occasional pieces of writing about plants and gardens, but this was at the start of my career as a botanic garden director. Early enough to not be obsessed with legacy, but late enough to be a little cocky about the importance and value of botanic gardens. By 2008, I’d been working in botanic gardens continuously for eighteen years, plus another nine months during a gap year in my university studies.

In Padua, I was being tested not by an oracle but by a novel [Robert Dessaix’s Night Gardens]. And I was up for the challenge. I had plenty of time on my hands, both on the slow train to Milan as well as over the weeks ahead. It was a chance to take stock and to return to Sydney better equipped to spruik the wonders and wherefores of a botanic garden. First, of course, I questioned the facts and the logic [of Dessaix’s arguments against botanic gardens] that’s what scientists do. We’ve all picnicked in one of our gorgeous Australian botanic gardens, so while it may not happen in Europe, where even walking on the grass is discouraged, it does happen. As for views and vistas, let me just list one: the unforgettable spectacle of the morning sun on Table Mountain, seen from Kirstenbosch Botanic Garden in Cape Town.

A museum? Well, my friends in the museum world are jealous of me because a botanic garden display changes each day as flowers open and leaves turn, and because every sense is engaged when you walk through our gate. Museum-like at times, but far more than that. I will grant the author his point about botanic gardens generally not being ‘produce gardens’, although later that same year I did eat a botanic garden. It was near Seoul, in the Republic of Korea, and the director of the private Hantaek Botanical Garden treated us to a meal of leaves and flowers picked fresh from his property.

As for god’s creation, I’m not qualified to talk to that, but I can say every botanic garden I’ve visited so far has a rather different objective, mostly allied to intrinsic beauty, science or conservation. Earlier in Night Letters, Dessaix writes about how we now seek paradise in untouched wilderness rather than in ‘the miniature mirroring of God’s perfection’. In Australia, he notes, ‘the Garden of Eden is sought in the rainforests of Far North Queensland and the deserts of Central Australia, not in the Royal Botanic Gardens of Melbourne, however idyllic they may be’.

Having moved from Melbourne to Sydney six years earlier, I was disappointed with this adverse comparison to my old workplace. In any case, again I would admit Dessaix has a point, of sorts. It’s true that nature devoid of overt western influence (to try to be precise with my words) is considered more Edenic or ‘natural’ these days than a western construct such as a botanic garden. In this sense, a botanic garden is more like an art gallery, or museum, or library. Yet it is, or at least can be, much more than all of them.

The problem, as I saw it on my way to Milan, was our inability in the botanic garden world to express why we existed, particularly in the 21st century, other than as a historical curiosity. That was my takeaway from reading that chapter of Night Letters. None of us running botanic gardens thought we were re-creating Gardens of Eden. Beautiful places for sure, but not some kind of utopian garden free of weeds and sin. The plants in a botanic garden do more than provide a bountiful or beatific backdrop. I wanted to unravel this further and find ways to express it through my own botanic garden in Sydney. To capture the essence of a botanic garden if I could, then preach that message from my pulpits – on radio, in magazines and through the design and planning of botanic gardens. And the influence of these public institutions should extend well beyond their fences, into the planning of urban green spaces and through to the care and protection of nature across the precious planet. There was work to do!

But first a confession. I too had low expectations of the botanic garden in Padua. Not due to concerns about paradises lost, or the intrinsic value of a landscape constructed by humans, but because I had only a week before in Florence seen a botanic garden in decline, achieving little more than being there. It was not enough, to me, for a botanic garden to be old and worthy. Not enough to have a few old trees and some Latin names affixed to plaques. Not enough to simply open the gates.

Even keeping those gates open was a struggle for some of the botanic gardens I visited, or tried to visit, in Italy that year. In the country where the modern botanic garden began over 450 years ago, most gardens seemed surprised to have a visitor in the 21st century. In Milan I went to the Orto Botanico twice but although advertised to be open it was shut both times. In Pisa, the garden was only open in the mornings, and I arrived after lunch. The botanic garden in Florence was open but difficult to find, hidden behind a forbidding high wall with an unlikely doorway. Rome was a little different, and more welcoming, but hardly drawing crowds away from the nearby ancient ruins and oddly positioned street fountains.

I couldn’t yet articulate my agenda for botanic gardens, but I knew what I didn’t like: ugly, dull and poorly curated gardens relying on their longevity for credibility. Visiting Padua restored my faith in the history and heritage of botanic gardens as something that could be nurtured and combined with other ingredients to create a good botanic garden. But what would make a great botanic garden, and the ‘World’s Best Botanic Garden’? That was the slightly tongue-in- cheek but deliberately provocative title of a talk I prepared on my return to Sydney. I wanted to explore what makes one botanic garden better than another. Indeed, what makes a garden a botanic garden? And most importantly why does it matter? Today.

Clearly the whole concept, or project, has been a successful one. While the modern botanic garden began in Europe, it soon spread with Europeans into the invaded and colonised world. The earliest outside Europe was most likely a 16th-century medicinal garden in the Portuguese colony of Goa, in what is now India. The Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, famous for its avenue of towering royal palms, was established in 1808 and is the oldest in the Americas.

Elsewhere in the southern hemisphere there was Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam Botanical Garden in Mauritius, established in 1736, or more formally as a botanic garden thirty-one years later. The East India Company’s Garden in Cape Town began as a vegetable patch in 1652, but by 1680 had risen to become that city’s botanic garden – a role superseded for the last century by the spectacular Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, at the foot of Table Mountain. Australia’s first botanic garden was established in Sydney in 1816. A year later, Bogor became the site of Indonesia’s first botanic garden.

Botanic(al) gardens were slower to take root in North America. The first (in Washington and St Louis) were opened in the 1850s, unless you accept the claim of Bartram’s Garden in Philadelphia to have been a botanic garden since 1728. And while there is a long tradition of ornamental gardening in China, the first gardens that could be described as botanic were not seen until 1860 in Hong Kong, and then 1929 in Nanjing.

Evidently, it can be difficult to determine what makes a botanic garden and when a garden becomes botanic. Most will be a little less ‘botanic’ in their early years even if established as such right from the start. The simplest definition of a botanic garden is perhaps that offered up by the International Association of Botanic Gardens in 1963 as a garden ‘open to the public and in which the plants are labelled’. That just won’t do today, compounded by the first element being only partly true in places like Italy. There have been attempts to expand that definition to include all the functions of a modern botanic garden, but these end up as a long list of attributes such as scientific research, plant collections, sharing of information with other gardens, exchange of seeds, education programs and, yes, public accessibility and plant labels.

My own preferred and self-crafted definition, at least before I headed to Italy in 2008, was ‘an inspiring landscape of documented plant collections, where every plant and setting has a purpose’. Typically, that purpose is for science, conservation or learning, but it may be equally for health or, let’s say, philosophy and culture. Anything really. This places the distinction between a botanic garden and a garden on its plants and the way they are arranged to fulfil a clear intention, and usually more than sheer beauty (although that helps).

I realise this definition is a little hazy around the edges. Surely, you argue, a local park has an oak tree to give shade and a rose to provide pretty flowers for a few months (and, less purposefully, an ugly, thorny stump for the rest of year). It’s a matter of degree. In a botanic garden the plant species, its source, its biology and ecology, and the story we tell about it are of utmost importance. In a good botanic garden, we tell many stories, and I want to share the best of these with you in this book.

Oh, and I’m your perfect guide by the way. Not just because I’ve headed up two of Australia’s major botanic gardens and held a senior role in the famous Kew Gardens of London, but because I’m an algal expert and wannabe journalist who started university to major in maths and physics. After more than three decades working in and exploring botanic gardens, I still feel like an outsider looking in. That means that I, like you, still have a sense of innocent wonder and anticipation.

Let me explain.

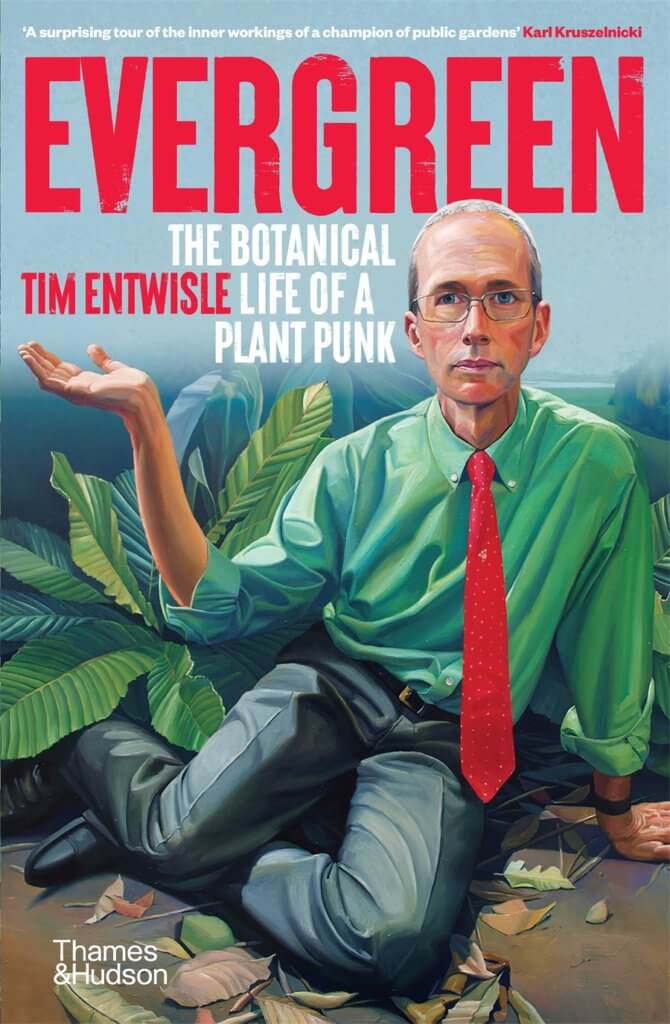

This is an edited extract from ‘Evergreen’ by Tim Entwisle.

Evergreen by Tim Entwisle is available now.

AU $39.99

Posted on August 15, 2022