Look in the space between the stars, what do you see? 1

Viewing the world as interconnected is core to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems and communities. As such, it is not only inappropriate but also impossible to truly learn about Indigenous astronomy without learning how the sky relates to the land, which all makes up what Indigenous peoples call Country – as captured by the Bawaka Country group in a 2020 paper:

Country includes lands, seas, waters, rocks, animals, winds and all the beings that exist in and make up a place, including people. It also embraces the stars, Moon, Milky Way, solar winds and storms, and intergalactic plasma. Land, Sea and Sky Country are all connected, so there is no such thing as ‘outer space’ or ‘outer Country’ – no outside. What we do in one part of Country affects all others.2

The story of the Celestial Emu exquisitely illustrates the holistic nature of Country and Indigenous knowledge systems.

On a moonless, cloudless night, away from the streetlights’ orange hum and the confines of tall buildings, the dazzling speckled infinite awaits. If you’re close to town, you might see vast darkness with the occasional twinkle. But if you’re far enough away from town, you will no longer see the dark but instead be overwhelmed by the light – point sources dancing and shimmering, performing an astonishing display in the vastness of the cosmos. It’s here we get to know the sky in all of its complexities and subtleties. No one knew this better than the First Astronomers.

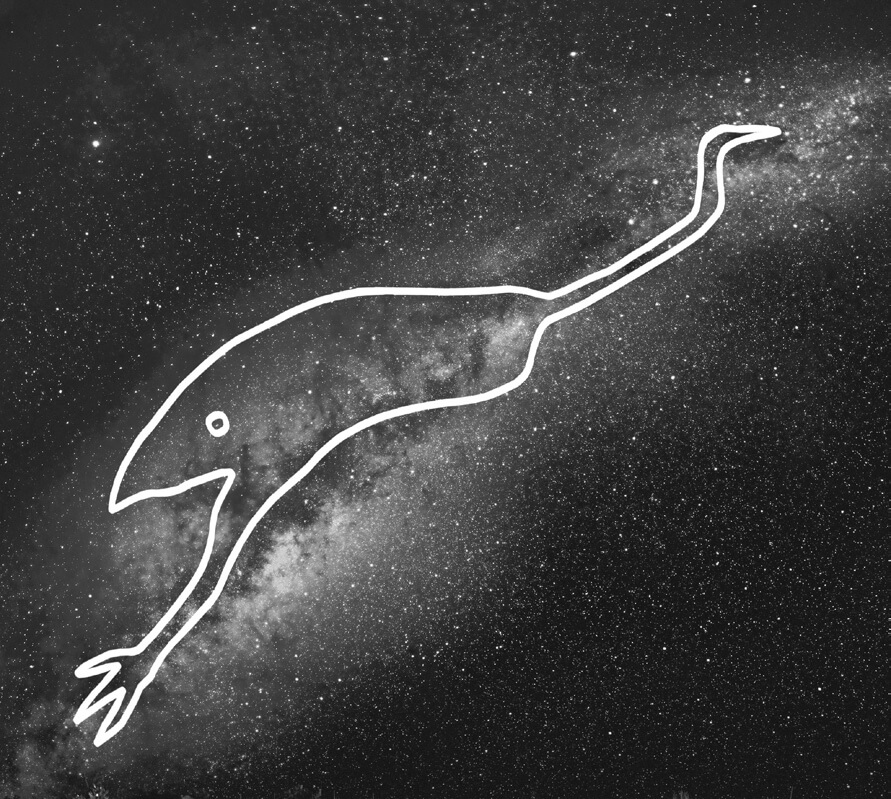

During the late southern summer, the Milky Way’s dominating light takes prominence over the entire night sky. As each day passes and winter approaches, the daylight reduces, and as the length of night grows, so too does the Milky Way’s presence in our skies. Among the bold, bright discs of light dwell pools of darkness. These uniquely shaped dark gaps are framed by a dazzling stellar spectacle. The combination of light and dark creates an undeniable feature with which nothing else in the observable sky compares (Figure 2.1). Different peoples see various creatures or places emerge from these features, each with its own meaning. To some, it is a big rip across the sky. To astronomers, it’s an entire galaxy shrouded by space clouds, behind which hides a supermassive black hole. The Wardaman people of the Northern Territory see the Milky Way as the Rainbow Serpent, accompanied by the Sky Boss and Earth Lady.3 The Yolŋu people of north-east Arnhem Land see a crow.4 For many Aboriginal nations, from east coast to west and from the Top End to the south, it is the Dark Emu (Figure 2.2).

The Dark Emu has many names. It’s sometimes referred to as the Celestial Emu. In Gamilaraay it’s called Gawarrgay, and its Dreaming tells us of dhinawan, with ‘Gawarrgay’ referring to the featherless, ceremonial Celestial Emu and ‘dhinawan’ referring to the land-dwelling, flightless bird.

These Dreamings are of particular importance to the Gamilaraay/Kamilaroi as the dhinawan is the nation’s totem. The Dreaming connects the dhinawan’s breeding cycle and its movement across Country, mirroring the movements of Gawarrgay across the sky.

In the months of April and May, Gawarrgay sweeps across the entire celestial sphere, legs and neck stretched out as though running. Kamilaroi man Ben Flick describes its positioning:

Just under the Southern Cross, you’ll see a dark spot. That’s the

head of the emu. In front of him is, of course, his beak, and as you

follow it down, you can see his neck in the dark spots of the Milky

Way. It comes right down to his body. You can see his legs and a

couple of eggs underneath.5

At the same time, on the land, the female dhinawan are chasing the males for breeding. After May, the dhinawan’s gawu (eggs) appear. These are early days for the gawu, before the embryos have had time to develop. The male dhinawan sits on the gawu, protecting the young. The dhinawan is important for Gamilaraay males, as the Dreaming teaches young men about their role in looking after the children in community, as the dhinawan look after the gawu.6 This is the best time for gawu to be collected, but people should only take what they need and leave the rest. If they wait too long in the season, the burrgay (emu chicks) form in the gawu. People should not disturb these gawu as the new generation of dhinawan is taking shape. In the sky, Gawarrgay’s legs disappear as he dives toward the horizon, signalling that the male dhinawan is sitting on the gawu on the land. The Celestial Emu is signalling to the Gamilaraay people to stop hunting as the eggs are now in incubation. As Flick describes it, ‘At that certain time of year, it’s time for us to go out and collect emu eggs. We go out into the bush, always leaving some eggs for next year and for generations to keep going.’7 Burrgay is also the Gamilaraay word for this time of the year (July), further illuminating the animal’s importance to Gamilaraay people and the culture’s holistic nature.

As the year progresses, Gawarrgay changes form and appears as a featherless emu crossing Country. Finally, in November, only the body of Gawarrgay remains, signalling that the dhinawan are currently occupying waterholes. Gawarrgay’s shortened form signifies to the Gamilaraay people to move across Country to access the same reservoirs as the dhinawan, but also to protect them from being overused and destroyed by the thirsty, cheeky dhinawan. When Gawarrgay reappears in February, people start moving from their summer camps and the waterholes to their winter camps. Just a few months later, the annual cycle of Gawarrgay, the dhinawan and the Gamilaraay people repeats.

Analysis of sixty-eight ceremonial grounds by cultural astronomers Dr Robert Fuller and Dr Duane Hamacher and CSIRO astronomer Dr Ray Norris found that the alignment of the Celestial Emu in the night sky throughout the year relates to the positioning and directionality of emu engravings on the ground.8

The sky knowledge connects to the food knowledge, which connects to the seasonal knowledge. It is relational, practical and cyclic. Through an Indigenous lens, everything is connected. This mirroring is a core belief for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. We see it in the Dreaming of Gawarrgay and the land dhinawan. Similarly, in Gamilaraay, Bulimah or Sky Camp is positioned behind the Milky Way, where camp sites, tribes and ancestral places reside.9 Same same but different. This mirroring is so essential to life on Country that it is immortalised in Country. The Big Warrambool is a flood plain located in southern Queensland that runs down to the Barwon River in New South Wales. The water plains of the Big Warrambool reflect the sky above and the land below, acting as a portal between land and sky. This place of Country holds further significance to the Gamilaraay people as it is seen as the start of their Country.10 In Victoria on and around Dja Dja Wurrung Country, a similar place is known in which a large pine tree acts as a portal intertwining people on Earth to the sky world, much like the Big Warrambool does for the Gamilaroi.11 The interconnected nature of Indigenous knowledge means Indigenous astronomy is never just about astronomy.

This is an extract from the latest in our First Knowledges series, Astronomy: Sky Country by Karlie Noon and Krystal De Napoli.

Notes

1 Participant 6, quoted in Robert S Fuller, Ray P Norris & Michelle Trudgett, ‘The Astronomy of the Kamilaroi People and Their Neighbours’, 2013, arXiv:1311.0076 [physics.hist-ph], p. 6.

2 Bawaka Country, ‘Dukarr lakarama: Listening to Guwak, Talking Back to Space Colonization’, Political Geography, 81, 2020, p. 2, <doi.org/10.1016/ j.polgeo.2020.102218>.

3 Hugh Cairns & Bill Yidumduma Harney, Dark Sparklers, H Cairns, Merimbula, 2004, p. 59.

4 For example, see Dawidi Birritjama, Cat and crow legend [bark painting], 1960, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, <artgallery.nsw.gov.au/ collection/works/IA42.1960/>.

5 Western Local Land Services, ‘Through Our Eyes: Dhinawan “Emu” in the

Sky with Ben Flick’ , Western Local Land Services, YouTube, 25 March 2014, <youtube.com/watch?v=LzFYFutiwoA>.

6 Rosie Armstrong Lang, private communication shared with Karlie Noon, July 2021.

7 Western Local Land Services, ‘Through Our Eyes: Dhinawan “Emu” in the Sky with Ben Flick’ .

8 Robert S Fuller, Duane W Hamacher & Ray P Norris, ‘Astronomical Orientations of BORA Ceremonial Grounds in Southeast Australia’, Australian Archaeology, 77(1), 2016, pp. 30–7.

9 Fuller, Norris & Trudgett, p. 9.

10 Lang, 2021.

Astronomy: Sky Country by Karlie Noon and Krystal De Napoli is available now.

AU $24.99

Posted on May 3, 2022