Discover the origins of coffee in this early extract from Around the World in 80 Plants, the sequel to Jonathon Drori’s bestselling Around the World in 80 Trees.

Ethiopia

Coffea arabica

Coffee

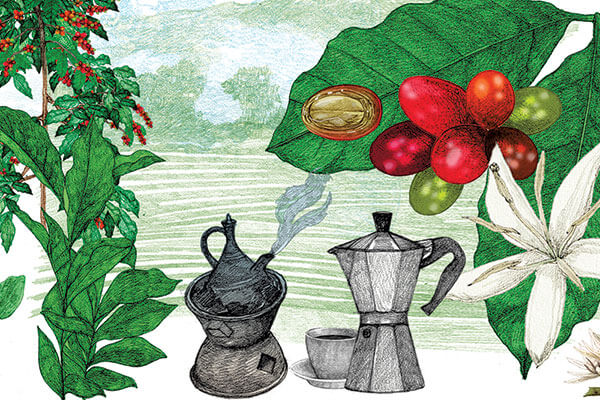

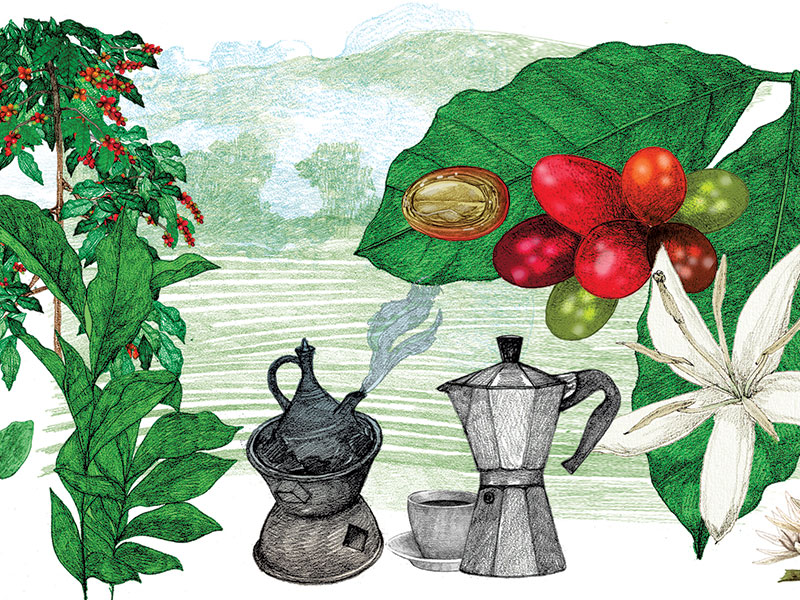

The little evergreen coffee tree began life somewhere near the forested mountains of southwestern Ethiopia, and its broad, elliptical leaves with crinkled edges, shiny and dark above and pastel-pale underneath, still prefer the shade. In full flower, coffee is a spellbinding but ephemeral joy; for just a couple of days, thousands of delicate white blossoms with a light fragrance of honeysuckle and jasmine can festoon a single tree. The smoothly oval fruits ripen to pillar-box red; their thin layer of edible flesh tastes of watermelon and apricot and surrounds a pair of deeply grooved seeds that are the familiar coffee ‘beans’. Coffee’s bright, sweet fruit have evolved to attract monkeys and birds, which ingest them, remove the pulpy parts of the fruit and excrete the seeds intact. Mercifully rarely, such beans have been gathered and sold as a luxury; for example, Indonesian kopi luwak coffee – considered by aficionados to be especially ‘smooth and earthy’ – is the, ahem, ‘product’ of Asian palm civets, which are often caught and traded for this purpose. Otherwise, all cultivated coffee is harvested by human hand; the fruit don’t suit mechanical harvesting because they don’t all ripen at once.

More than 1,000 years ago, thanks to genius or good fortune, boringly unscented beans that had been separated from their fruit and husks were roasted, pounded and added to hot water. The resulting fine-flavoured, stimulating yet non-alcoholic brew spread via Yemen throughout the Islamic world and the Ottoman empire. The story goes that in about 1600 coffee’s association with Islam caused Vatican officials to dismiss it as ‘Satan’s latest trap to catch Christian souls’, but Pope Clement VIII supposedly tried some and gave coffee his blessing because it would have been ‘a shame to let infidels have sole use of it’. What a charmer!

By the mid-seventeenth century coffee houses were popping up around Europe, and in London especially they became places for men to discuss business and politics, in contrast to the chocolate houses (see

page 71), which were more light-hearted and welcoming to women. Over the centuries, many cultures have developed coffee rituals, sustained by beguiling paraphernalia and nerdy choices of grind and provenance. Ethiopia has a particularly elaborate ceremony. Amid wafts of incense, beans are freshly roasted over glowing charcoal and pounded at the table with cardamom or other spices. The resulting intense, dark drink is served with … popcorn. It’s a delightful experience for those fortunate enough to live within reach of an Ethiopian café, but perhaps not just before bedtime.

The coffee tree didn’t develop caffeine for our benefit. When its leaves die and drop, their caffeine leaches into the soil, impeding the germination and growth of competing plants, and it is also a defence, sometimes a lethal one, against various insects and fungi. It is therefore surprising that coffee and even some unrelated citrus plants put caffeine in their nectar, which, after all, is meant to reward insects for ferrying pollen to other plants. It turns out that the merest dash of caffeine, below the threshold that bees can sense, helps them to remember the plant, making them more likely to return to it. The flowers shrewdly dispense just enough caffeine to be pharmacologically active but not enough to be bothersome.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, Asian production of Arabica coffee was wiped out by a fungus: coffee leaf rust. Groves were replanted with ‘Robusta’ (Coffea canephora), which was immune, and although it has a harsher taste than Arabica, it is now widely cultivated. Existing coffee strains are at risk once more, from climate change and the new pests and diseases that come with it, but there is scope for breeding new varieties. There are more than 120 wild species of coffee, most of them in tropical Africa. They have fascinating flavours and contain differing amounts of caffeine, and some of them tolerate heat and drought, or cope with different soils or plant diseases, yet most are themselves threatened by climate change or forest loss. It feels unfair that much of the burden of protecting this vital source of genetic diversity for one of the world’s most valuable commodities should be borne mainly by African nations.

Around the World in 80 Plants will be available on April 15. Text by Jonathon Drori and illustrations by Lucille Clerc.

AU $39.99

Posted on March 3, 2021