In this extract from his new bestselling book Chromatopia, author and master paint maker David Coles looks at the origin of ochre – believed to be the first pigment used to create human artworks.

The oldest human artworks still in existence are vivid depictions of animals, humans and spirits that were created using ochres. There is evidence of their use as far back as 250,000 years ago. Ancient ochre artworks are found all over the world, from the earliest cultures of India and Australia to the famous cave paintings of Lascaux in France.

Naturally occurring iron-containing ochres of the earth provide a wide range of yellow, red and brown colours.

The natural mineral could be collected or dug-up and then simply ground against a harder rock and water added to make fluid. Later civilisations refined this process to include washing the ochre of impurities, drying and then grinding to a fine powder.

Yellow ochres are an impure form of iron oxide called limonite. They can also be roasted to produce other hues

by placing on a fire or in an oven. A moderate heat turns the yellow to orange; stronger heat makes the colour turn red. These roasted red ochres are often called ‘burnt’ (for example, burnt sienna). Naturally occurring red ochres are richer in anhydrous iron oxide called haematite. They also vary widely in shade, hue and transparency.

There are many earth pigments whose specific colour comes from natural mineral admixtures. The pigments known as ‘umber’ contain iron plus manganese oxide that lends a greenish hue. Iron-oxide-free earths are not strictly ochres, but it is important to include them here as their use alongside the true ochres is significant throughout history; white earths from pipe-clay, black earths of manganese and the light green pigment terre-verte (green earth) from mineral celadonite.

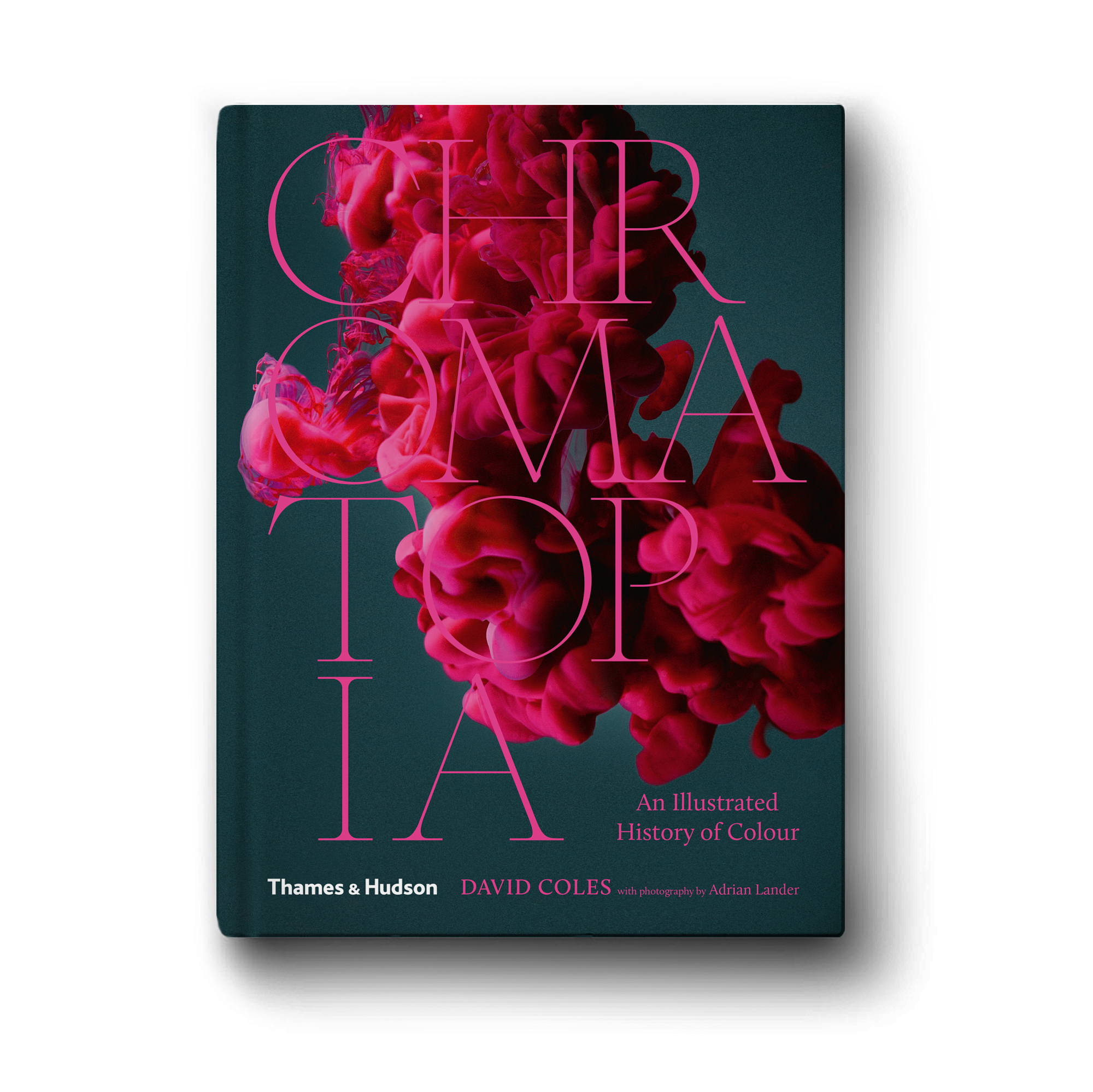

Text © David Coles from CHROMATOPIA, published by Thames & Hudson.

Photographs © Adrian Lander

Posted on September 7, 2018