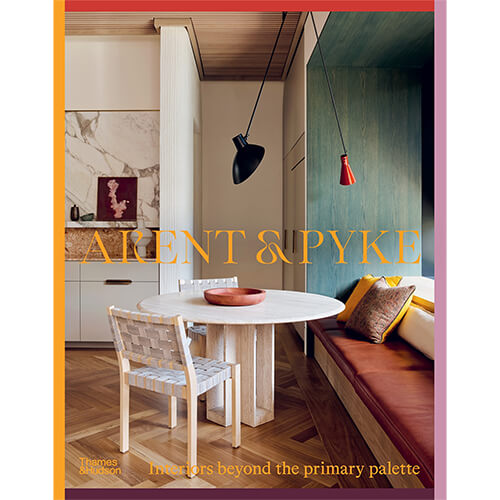

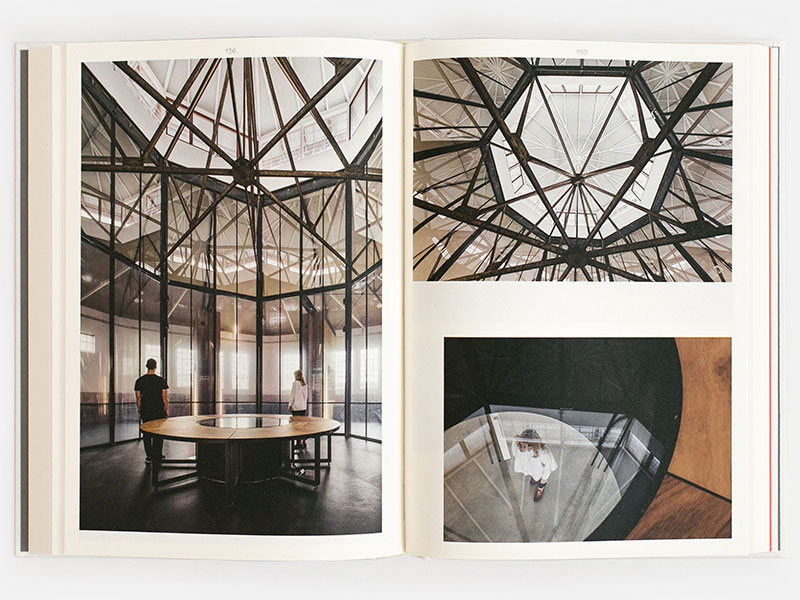

This is an extract from the introduction of Arent & Pyke: Interiors Beyond the Primary Palette by Juliette Arent and Sarah-Jane Pyke.

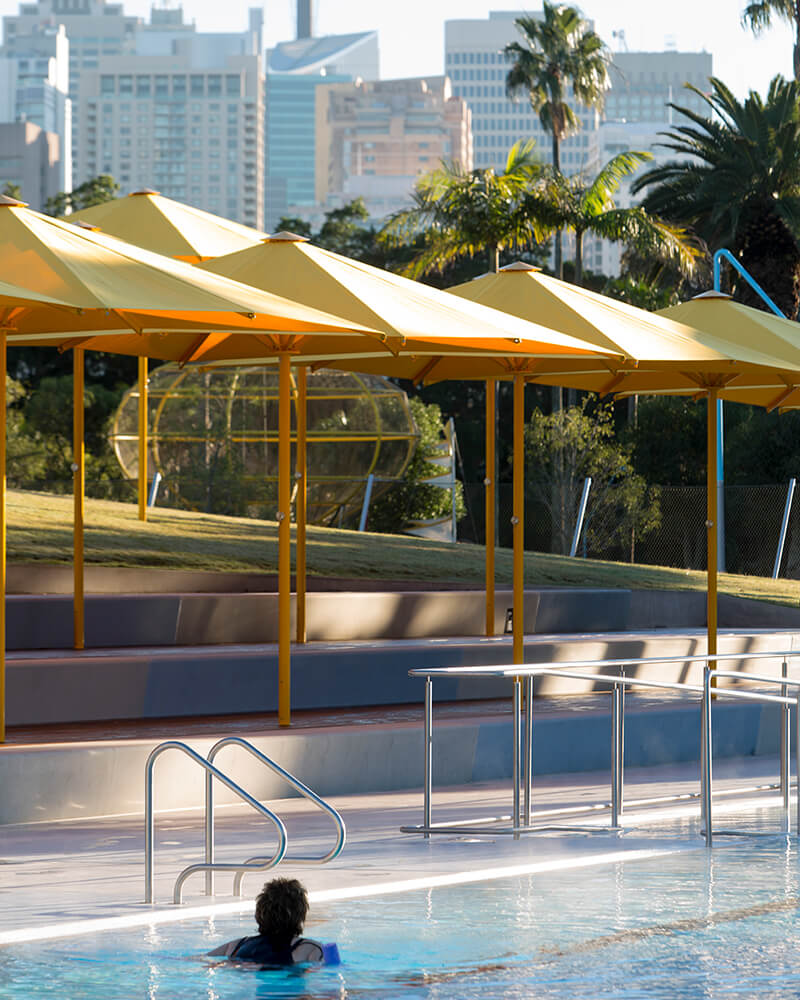

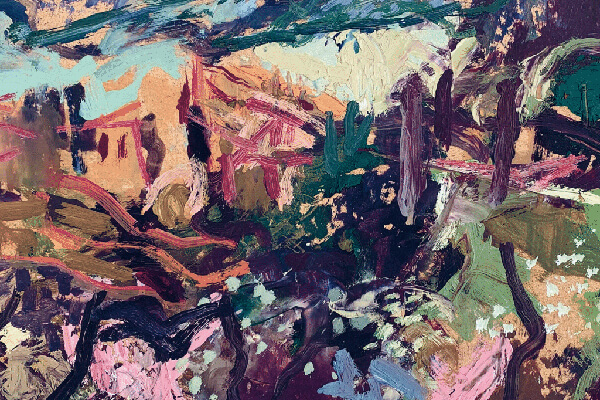

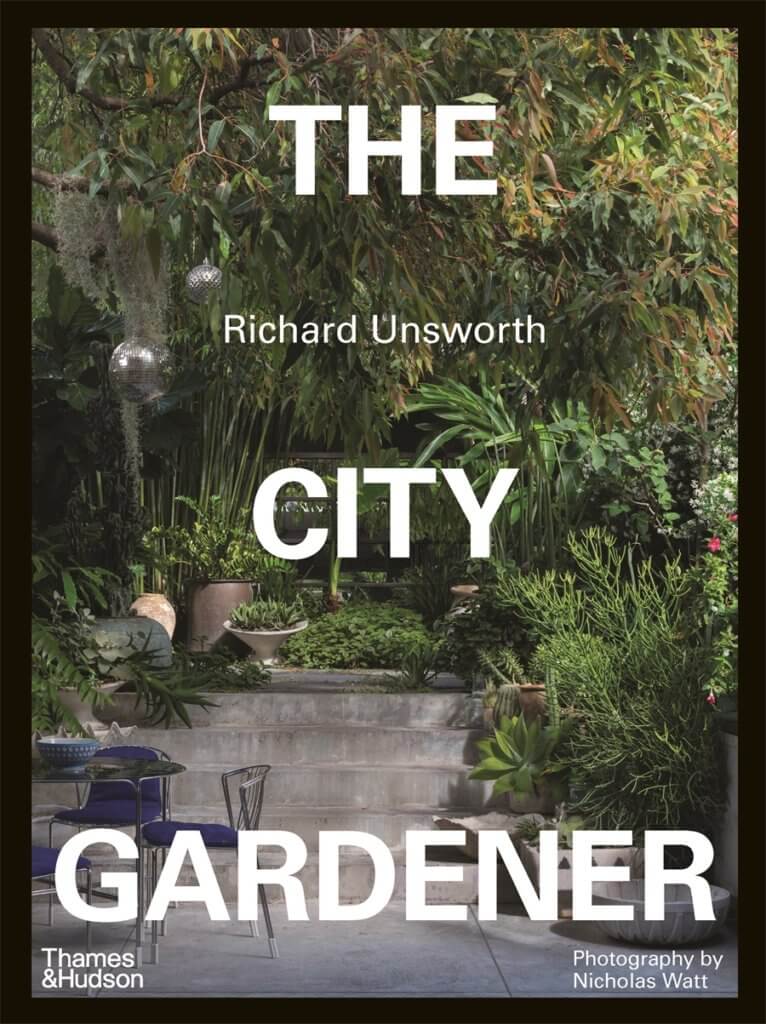

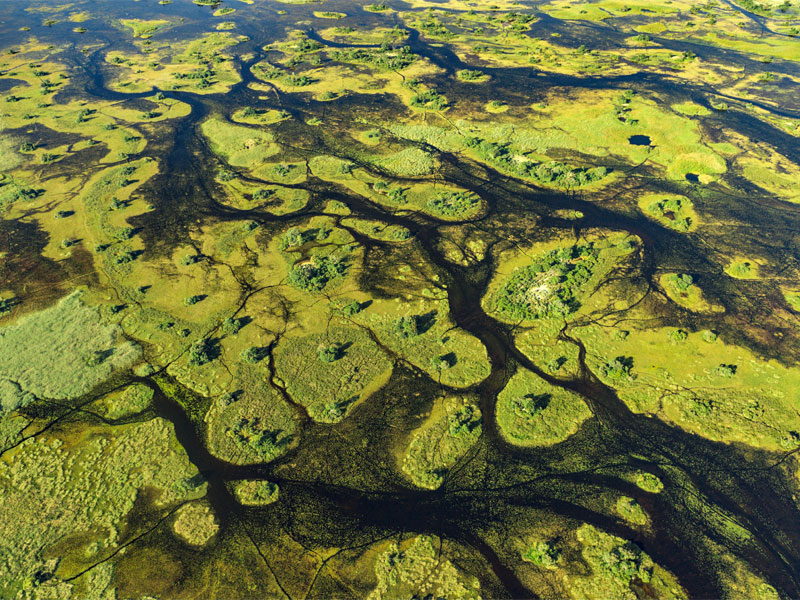

We can still remember the feelings one particular suburban Sydney backyard stirred in us. Standing amid its myriad greens, we were transported to another place, even time. This garden could have been a fictional wonderland or the grounds of an Italian villa, such was its enchanting quality. Part of this magic stemmed from the owners’ deep connection to what they had created, and part came from the house’s connection to its surrounds. The building and landscape seemed beautifully entwined.

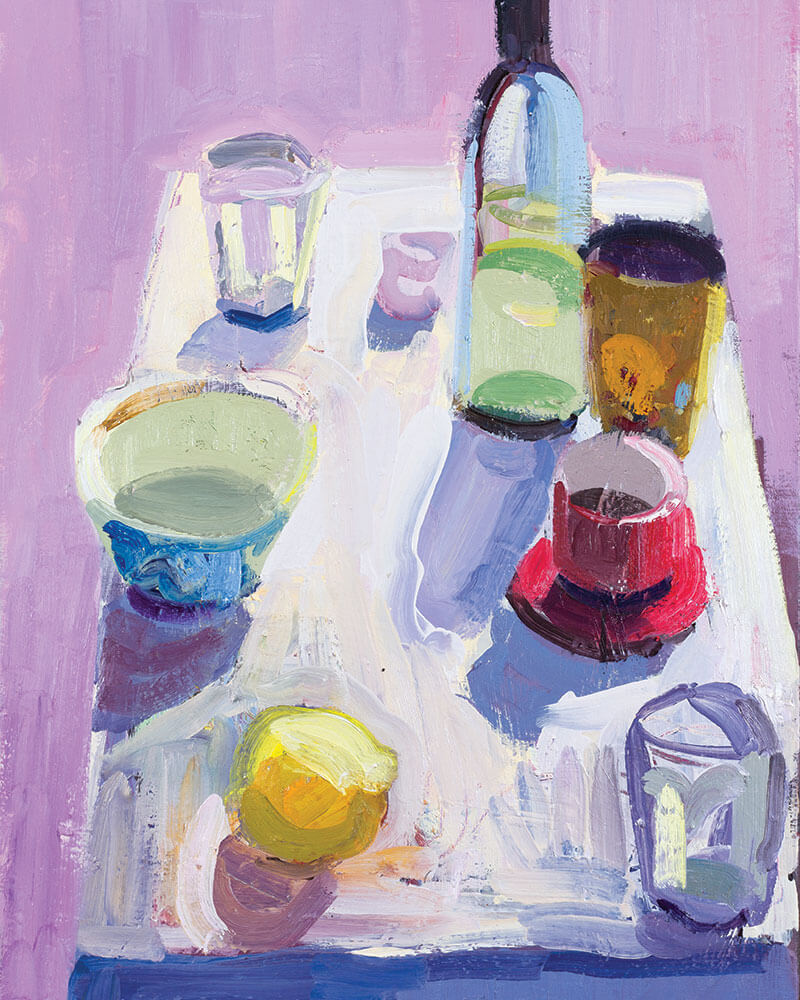

Our response as designers was to enrich those connections, and in a decorative sense the incorporation of green was a natural choice. But the significance of that colour extended beyond the decorative – it became woven through the built-in elements in an evocative layering of hues. The variegated greens of a checkerboard terrazzo floor brought a sense of nostalgia and an other-worldly mood to echo that of the garden. Deep green joinery ensured the very fabric of the house resonated with this tranquil yet vibrant tone. We painted the walls a misty green that blurred the division between interior and exterior, and the treatment of colour in this house became an immersive experience, as alive with feeling as the shifting canvas outside.

For us, to talk about colour is to talk about memory, but also meaning, energy and emotion. To write a book that references colour in its title is to discuss so much more than a choice of floor tile or paint finish for a wall, although these have their place here too. It is part of a larger and deeply nuanced conversation that we have been engaged in for years. And it begins with the concept of joy.

Everything we do is to create visceral joy – that inner thrum of delight where instinct speaks over intellect, heart over head. A beautifully designed space has the power to generate a sense of belonging, comfort and freedom that uplifts your spirit. We believe that power extends even further – a space that fills you with joy can transform how you live.

While it may sound very ‘big picture’, for us this belief is grounded in rigorous attention to the smallest details. The objects that tell our stories, the colours that call to our senses, the materials that evoke certain moods – all these play a vital part. But even more than that, our focus is on the day-to-day experience of people’s lives. We are constantly thinking about the reassuring rituals and intricacies of domestic life – where people make their tea and coffee, where they prepare school lunches, where they place their bags when they get home. We are also deeply interested in the places of connection – where people sit to unwind, to gather, to entertain – and the way people engage with one another in their own space.

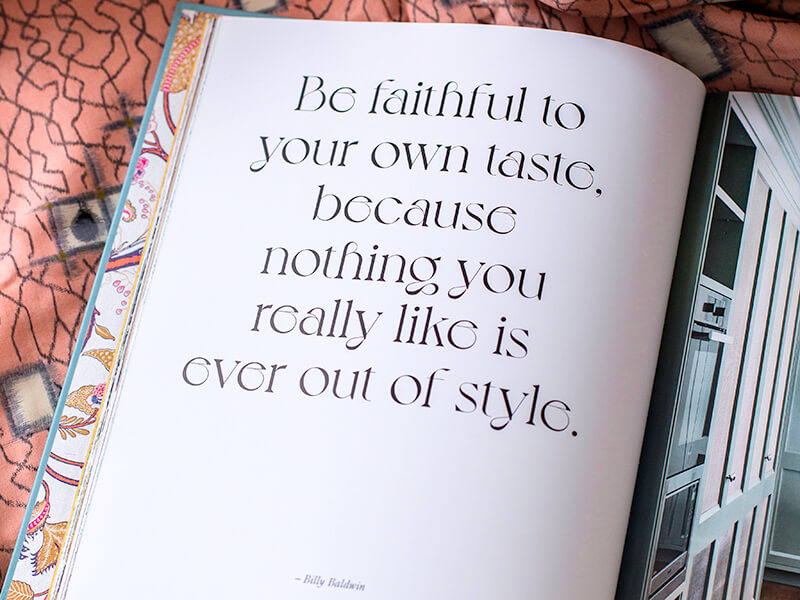

Fifteen years ago, when we formed Arent & Pyke, no one was really talking about how design made you feel. The focus was on aesthetics and the debates were around trends – old school versus new school, minimalist versus decorative – yet there didn’t seem to be enough interest in how a design could impact your life. Or how a house could be lovingly crafted for the unique lifestyle of a family.

From the start, our approach has not been concerned with trends or generic solutions but rather the dynamic, spirited, colourful and very personal appeal of real-life spaces – the sort of spaces we would like to live in. When we met, we recognised that we shared the same energy and entrepreneurial drive, and the same passion for life – not only the life we wanted to create for ourselves, but the life we wanted to create for our clients. Our intention was to create authentic, meaningful spaces full of verve and vitality that lift the spirit and nurture the soul. It still is, and today we share that vision with our team and our extended network of collaborators.

While ‘emotional connection’ and ‘wellbeing’ have become industry buzzwords, we are proud to be leaders in the conversation that now revolves around them. For us, wellbeing and joy are intrinsically linked, and we believe there is much to be learned in terms of the impact great design can have on our lives. We’re keenly aware of how much our environment affects our sense of wellbeing, and we want to offer people the best way of living, creating healthy, low-impact homes that help them thrive.

Now, more than ever, that seems essential. Since we started our business, we have witnessed a shift in values to a more inward-looking focus that is literally closer to home – to our local community, our friends and family. Never has the safety and comfort of home been more important, or the need to create joy at home more necessary to strengthen, nurture and

replenish us before we look outwards again.

Writing this book has been a chance to reflect on the path of Arent & Pyke – not only how far we have come but also what we want to bring to the future. We are delighted to share our philosophy, our approach and our designs in these pages. For us, the building blocks of a project are not the bricks and mortar but the intangibles that make up our ethos as a business: the transportive and immersive roles of colour, the creation of joy and forging of an emotional connection, the character and spirit of a house – its heart and soul – and that special alchemy that occurs when it all comes together in a unique, magical blend. These ideas are the touchstones of our studio, and the projects we have selected here illustrate how we express those ideas and bring them to life.

We hope that viewing our projects through this lens gives them an extra dimension and prompts a different way of thinking about the spaces we live in. We have never been interested in decoration for decoration’s sake – for us, a design should go beyond beauty and function to achieve a timeless, uncontrived quality that ensures a house belongs to those who live in it.

This book explores the rich physical aspects that we know colour can bring to interiors. It ventures into a surprisingly evocative spectrum of soft and subtle shifts in tone but, further than that, it taps into the emotion of

design. When a home is brought to life through the colour, character and spirit of its different elements, everything is enriched and all the senses are engaged for a full, joyous living experience.

The experience of joy can be both immediate and far-reaching. It can be as simple as feeling inspired by the colour on a wall and as wonderfully complex as the way a well-designed space can enrich your life.

JOY

THE CONSIDERED CRAFTING OF SPACES THAT LIFT THE SPIRIT AND NOURISH THE SOUL

It sounds simple – we want people to feel happy in their home. But behind this is a deep understanding of the complex psychology of space and the lifestyle and personal journey of each client. We harness all the elements we work with – colour and pattern, material and textile, light and art, line and form – to individually shape each special space.

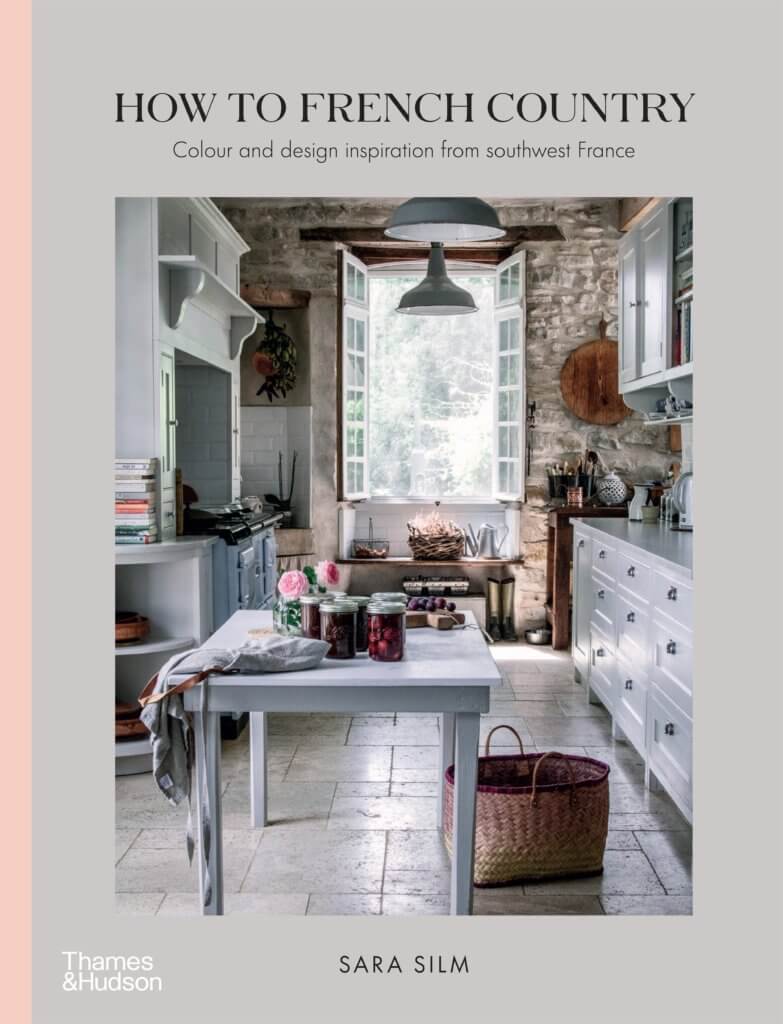

Home should be a place of nurturing and nourishment. It should be a sanctuary of peace, comfort and security where you feel grounded and free to be yourself. Crafting that place is about fostering an emotional connection and a sense of belonging. Your heart space. Creating visceral joy is at the heart of all our work. Our focus on how a space feels begins with an appreciation of how people experience living there. Home is the place for recharging and relaxing, and with this in mind we consider both the spaces for interaction and those for reflection. We focus on where people come together, such as the kitchen, living and dining areas. This is where all the action happens and where some of the most joyous moments occur. For us, the kitchen is far more than a functional zone and we strive to make it a warm, vibrant place to congregate, rich with colour, character and tactile pleasure. In the same way, the bedroom is more than somewhere to sleep. It is also a place for repair and recharging, so we design it as a true retreat

zone and emotional balm.

Joy and wellbeing are intertwined, and for us a happy home is a healthy home. We want to craft living spaces that soar with feeling and feed the soul. Creating a room that sings with colour sounds simple, yet the emotions it sparks are far from it.

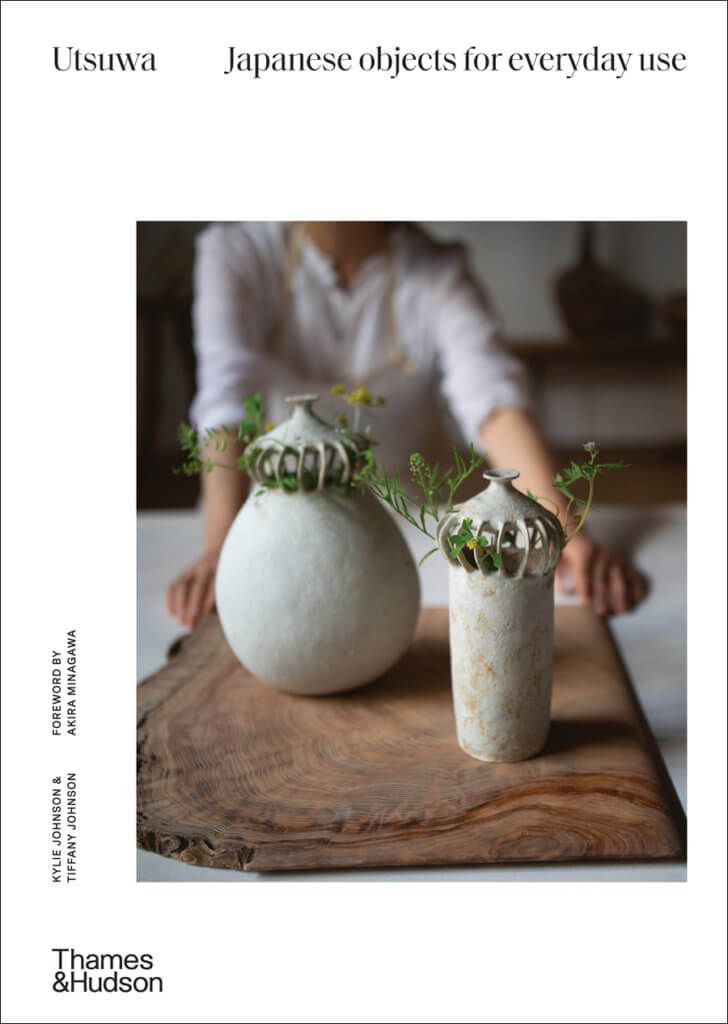

COLOUR

THE INFINITE POSSIBILITIES FOR THE EMOTIVE AND THE IMMERSIVE

The meaningful role colour can play in bringing a space to life is a continual source of inspiration for us. We weave colour through the entire fabric of a house at every stage of the design process. Even then, the placement of one last richly hued accessory or artwork can be the element that draws the whole design together. The influence of colour is ongoing and we never stop thinking about it.

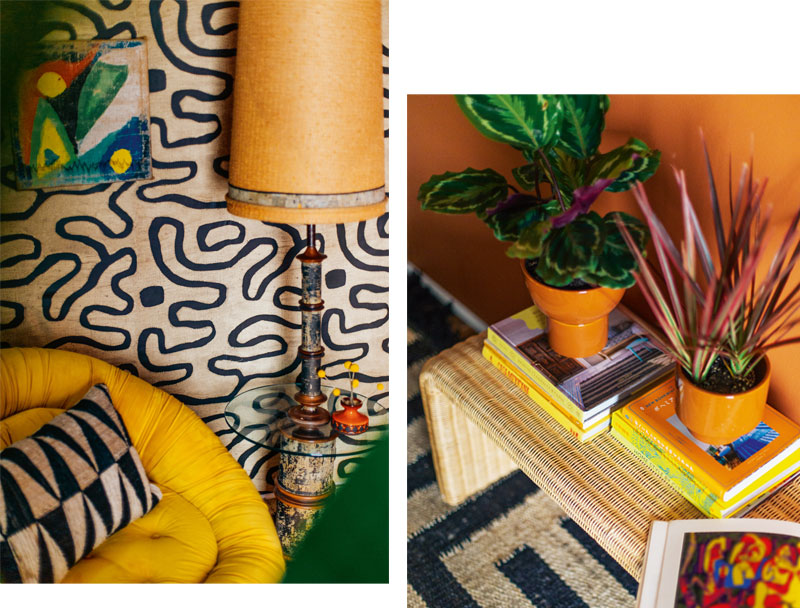

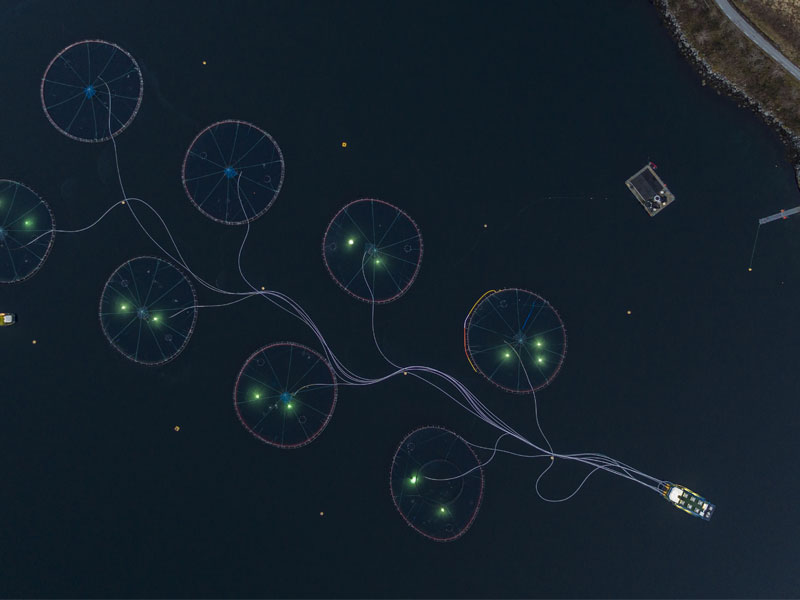

We use colour as a device to evoke particular moods and shape the experience of a space, playing with its look in different light to soothe or energise, nurture or revive. We use it to unify spaces, linking new parts of a house to old ones, or crafting a connection between interior and garden. Our approach is not to add a ‘pop’ of this or ‘block’ of that – for us, the greatest power of colour lies in its immersive effect, a painterly quality that envelops you so its presence is felt as much as seen. Adding a soft pink tint to the walls of a room can give it a rosy glow that transforms the room – and the feelings it provokes.

Our focus isn’t necessarily on the bright and bold colours, although these have their own significant impact. The softer, nuanced tones of the tertiary palette, whose language lies in delicious words like nougat, butter and olive, can unlock the door to a world of emotions. We work a lot with colour combinations, exploring the way different hues interact – room to room, piece to piece – to conjure up an entirely new sensibility. At the heart of it all is our desire to elicit a response, and whether we use colour to create harmony or contrast, it is always with the intention to lift the spirit.

CHARACTER

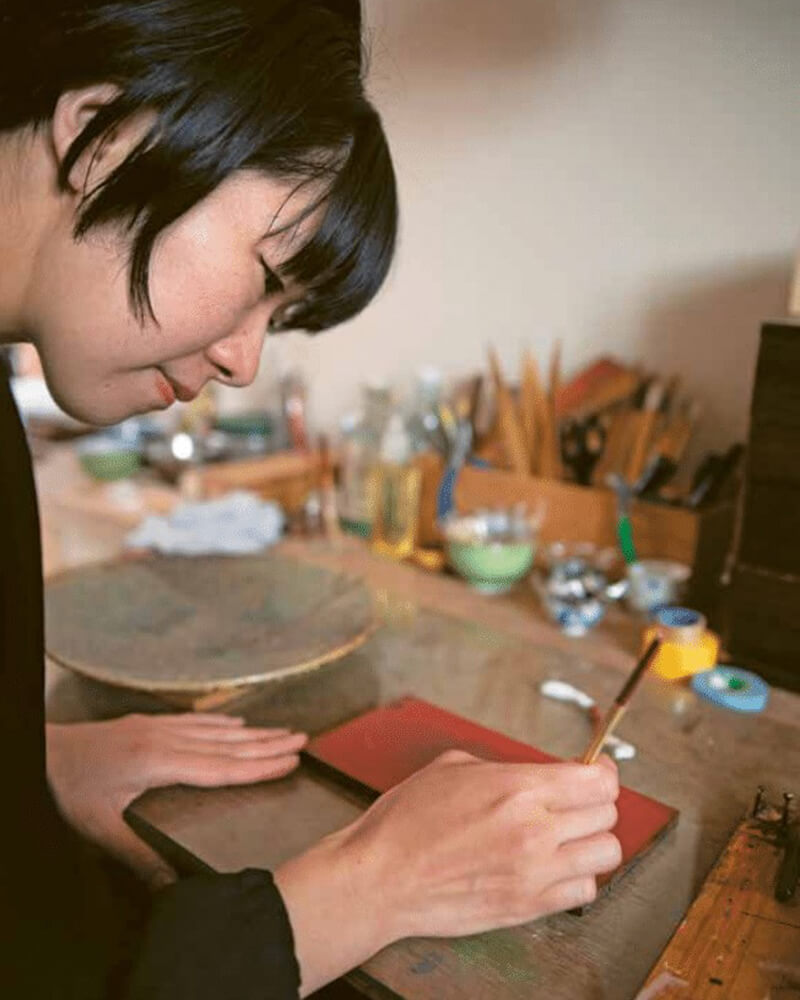

THE MEANINGFUL OBJECTS, ARRANGEMENTS AND ELEMENTS THAT TELL THE STORY OF A SPACE

The character of a home comes from the elements that reveal its personality and tell its story, from architectural lines and forms to cherished family pieces. Sometimes our design is responding to a story that is already there, such as with heritage buildings. Here, we try to distil the essence of the house’s character and meet that in the contemporary language of detail and joinery, subtly referencing the mood of the past while reflecting the client’s lifestyle for the future.

At other times we are helping clients to create a new story. Incorporating their own belongings – a favourite artwork, a souvenir from their travels – helps us do this. Not everyone has these to begin with, so during the design process we encourage clients to think about objects in a new way, beyond their decorative or functional role and in a more emotive realm. The story of an interior grows richer, more authentic and more interesting when personal, meaningful elements are woven into it. In this way, the design choices made today can become potent new memories in the future.

One of the most natural and pleasing ways to bring character to a space is through the process of ageing. It might be an old timber table that shows the knocks and cuts acquired over the years, or the faded upholstery of a favourite chair, or a brass doorknob that reveals the frequent attention of human hands. The nicks and patinas are tangible marks of the passage of time and the rituals of life and as such are imbued with meaning. It is one of the reasons we love working with materials like timber, terrazzo and marble – the connection they offer us to nature and its inevitable cycle

brings a strong sense of comfort. To us, a home that reflects the beauty of time passing and the ephemeral nature of things is a celebration of life well lived.

SPIRIT

THE HEARTBEAT OF A HOME, THE ESSENCE AND DYNAMIC LIFE FORCE OF A SPACE

We want to create homes that are full of spirit and hum with life to reflect the lives of their owners. Much of our work involves imbuing spaces with energy, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they have to be lively and vigorous. Different spaces call for different moods, and crafting those moods involves using a range of elements from artworks to the modulation of light. Scale can be a persuasive tool here – we might introduce smaller pieces and more of them, or opt for fewer pieces in a larger scale to make a room feel calmer.

Along with colour, we use pattern to enrich the spirit of a space. We are particularly fond of asymmetric, organic lines that take their cue from the natural world, breathing life into a design, relaxing formal layouts and promoting a sense of ease. And for us, pattern is as much about the inherent details of materials as it is about fabric. An abstract print on a bedhead can lend a playful quality, but the swirls of figured marble, the mix of colours in terrazzo and the pleasing grain of timber also bring their own dynamic and offer the comfort of their tactility. The sensory experience of a home is part of its appeal and we are constantly considering these elements for our clients – how a cushion feels to hold, how a floor feels to walk on. We literally feel our way around each project.

A spirited home is a joyful home, and we believe that central to this is a lighthearted sense of design that exists beyond the practical and purposeful. Home is not the place for the symmetrical and stitched up or the overly formal and tightly wound. We like to incorporate touches of whimsy and optimism purely for their beauty and the happiness they generate. A dreamy wallpaper print, the cheeky form of a chair, an unexpected artwork – these are the moments in a house’s life that surprise and delight.

ALCHEMY

THE ENCHANTING BLEND OF ELEMENTS AND THE IMPACT OF THE INTANGIBLE

Where you drop your bag when you get home, where you make your coffee, sit to read, hang your bathrobe – we delve into and delight in these intricate, important domestic details. We take a deeply empathetic approach in working with our clients, listening to and learning from them, and putting ourselves in their shoes so we can deliver a personal understanding of their lifestyle. The resulting design should feel familiar and intuitive, uniquely crafted to suit the people who live there. Rather like a magician’s sleight of hand, it should feel effortless in its experience without revealing all the planning and work behind it.

There is another layer to this magic. We believe there is an alchemy at play in the best of spaces, where all the elements – volume and texture, light and colour, architecture and object – combine to create something truly special that is greater than the sum of its parts. It is a holistic synergy we strive for, considering all these elements together throughout the design process. Added to this are the intangibles – the eliciting of emotions, the building of character, the injection of spirit. The evocative blend of things you can see and things you can feel – this, for us, is the alchemy of joyful design.

Arent & Pyke: Interiors Beyond the Primary Palette by Juliette Arent and Sarah-Jane Pyke is available now.

AU $80

Posted on December 15, 2022